Mozambique and European Union sign Strategic Digital Partnership in Brussels

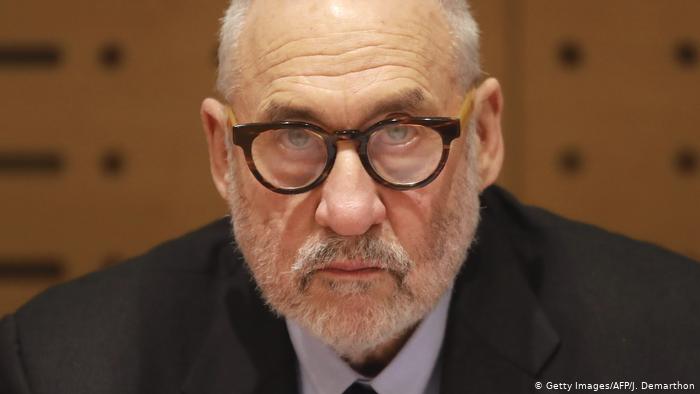

Nobel laureate warns Mozambique about danger of excessive debt

File photo: DW

2001 Nobel laureate for Economics Joseph Stiglitz warns Mozambique against taking on excessive debt in the expectation of natural resource revenues, especially natural gas.

“A disturbing trend in economies when we have large reserves of natural resources is excessive debt, because of confidence that there will always be money to pay their debts,” former vice president of the World Bank Jose Stiglitz says.

Stiglitz was speaking in Maputo yesterday on the topic “Mozambique and the Future: Paths for Sustainable Development”, at the Mozambique Social Economic Forum (Mozefo), a two-day event which ends on Thursday ( 21/11).

The prospect of massive gains makes natural resource-holding countries a seductive target for international bankers, he said.

“If Western or Asian banks believe that Mozambique will be able to repay loans because they have a lot of natural resources, it is only logical that they will be tempted to lend money, often under terms which are detrimental to the country,” Stiglitz said.

Diversification

The economist recommended rather the diversification of the economy, using natural resource revenues as a catalyst to create more jobs and generate more income for families.

“Extractive activity creates very little employment, and it is illusory to think otherwise, so money from this sector must be [put] at the service of the [general] economy,” he added.

Poor management of natural resource revenues, he continued, will intensify inequalities and social tensions because the gains from the extractive sector will be enjoyed only by a small elite.

On the other hand, intensive flows of foreign currency relating to investments in the exploitation of natural resources may cause harmful exchange imbalances to the export capacity of other sectors of the economy, he warned.

Sovereign wealth fund

The 2001 Nobel laureate for economics advocated a sovereign wealth fund backed by natural resource revenues as an instrument for investment and for cushioning crises caused by volatile energy prices, or even by a ban on fossil fuels in various economies.

“In a few more years, Mozambique will not be able to sell its coal to some economies, because they will already have fossil fuel policies in place,” he said.

The IMF expects Mozambique’s public debt this year to rise to 108.8% of GDP, remaining above 100% of GDP until 2023, and recommends, taking debt sustainability into account, that the country’s funding be based on external grants and highly concessional loans.

On 7 November, Fitch ratings removed Mozambique from the list of countries in default, giving it a CCC rating, the third worst level, after the country reached agreement with sovereign debt holders.

The bonds represent about a third of the US$2.2 billion ‘hidden debts’ contracted with state guarantees by the previous government between 2013 and 2014 in a case currently being tried in New York over suspected corruption and illicit enrichment, which has already led to the detention of international bankers and figures linked to the Mozambican elite.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.