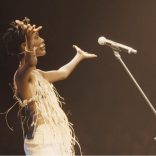

Mozambique: Lenna Bahule is about to launch 'Kumlango' in Casa Velha, Maputo

Mozambique’s Tete city turns 63

The City of Tete celebrated its 63rd Anniversary this Monday (21) in a festive atmosphere.

In the speech preceded by the placing of a wreath in the Praça da Independência, Tete mayor César De Carvalho reiterated his commitment to continue to better serve the citizens by promoting a work culture at all levels in the institution.

He explained that the successes achieved in this mandate, which began in 2019, are the result of an immeasurable contribution from the municipalities and the local business community, to whom he professed gratitude.

“We are fully aware that, without the support of all citizens and our partners, these achievements would not be possible,” he said, pointing to the rise from Class C to B as unequivocal evidence of Tete’s development.

In a descriptive speech, the president of the municipal council drew an X-ray of city hall’s performance in all areas, singling out the acquisition of means as a great triumph.

“It was with these means that today there are openings of roads, paving of streets among other activities linked to the improvement of access roads depend exclusively on us because we have our own means, which makes it a lot easier for us,” he concluded, renewing the request for the contribution of every member of society in the construction of the city.

During the ceremonies, which were attended by the Governor of the Province of Tete, Domingos Viola, civil servants who excelled last year were awarded, and there was a parade of some of the resources acquired in this term of office, including excavators, cistern tankers and trucks.

In addition to a municipal police march-past accompanied by military band, the ceremonies celebrating the city’s 63 years were enlivened with cultural activities such as dance and theatre.

Source: Municipality of Tete

History and Heritage – Tete City

The city of Tete, located in the province of the same name, is one of the oldest urban centres in Mozambique.

Located on the right bank of the Zambezi River, on a plateau about five hundred metres high that descends to the river bank, legend has it that the place was previously an extensive cane field (‘mitete’ in Nhungue), hence its name.

The first made by the Portuguese houses appeared around the second quarter of the 16th century, at a Swahili trading post that supplied the caravans that travelled between the southern Mozambican coast and the region.

The concession of the place, and of a vast surrounding area, was made by Monomotapa [Mwenemutapa], lord of those lands.

Frei João dos Santos visited the village at the end of the 16th century, noting in his reco rds that he found a church, a stone and lime fort with seven or eight artillery pieces (São Tiago Maior, from the 16th-17th centuries), and a population of “more than six hundred Christians, of which forty were Portuguese, and the other Indians and Kaffirs”.

The nucleus grew slowly – as was always the case with the fragile Portuguese presence in that deep interior – supported by gold mining and its location on the Zambezi River, at the time the main route of communication. Frei João dos Santos wrote that “the residents [of Tete] come to this trading post [Feitoria] of Sena to use their gold to buy goods there”. Later, commercial activity would switch to ivory and then to slaves, based on a circuit that linked the coast and the Mwata Cazembe in Congo, of which this place was a part.

By royal charter of May 9, 1761, Tete was elevated to a village (with a garrison of one hundred soldiers), succeeding Sena as the capital of Zambézia.

A century later, its new fortress was completed, the work of Captain General Caetano de Melo e Castro, with the name Fort of D. Luís. The place was also known as the São Pedro de Alcântara or Carrazedo Fort, due to the fortification that was built there during the first half of the 19th century.

An oil painting by Thomas Baines, dated April, 1859, represents the constructions of previous centuries and the banks of the Zambezi, with the Fort of São Tiago Maior clearly visible.

At the end of the 19th century, Portuguese sovereignty of the town was still unstable, threatened by the semi-independent Afro-Goan ‘prazeiros’ [land tenants] who engaged in trade with the interior. In fact, Tete’s ‘peripheral’ reputation would persist until independence, and to a certain extent lingers even today.

In 1917, the Báruè revolt beat a path right to its doors, threatening an occupation that was narrowly avoided.

Forty-some years later, in the midst of the independence war, the city was the headquarters of the Portuguese military command for this area, and became familiar with the roar of weapons on the opposite bank, right in front, with the attack on Chingozi airport in 1972.

Growing only slowly during the 20th century, due to the difficulties of its location, Tete by 1952 had only about 38,000 inhabitants. City status, granted in 1932, was only officially confirmed on March 21, 1958, by decree 13,043 (Boletim Oficial 12/59).

The evolution of Tete’s urban layout can be precisely reconstructed thanks to a number of sources.

These include the Cadastral Plan of Villa de Tete, from 1912, at a scale of 1/10,000, meticulously labelled and depicting a regular and elementary grid by the riverside; the Plan of Projected Zones; photographs of the square and drawings of its fortification published in Monumenta (no. 6, after p. 73); the 1950 Urbanisation Plan (possibly the Tete Urbanisation Plan); and the 1973 Urbanisation Plan by Hidrotécnica Portuguesa.

Throughout the 20th century, Tete’s prosperity depended essentially on the coal mining industry in Moatize, as well as on the production of hydroelectric power from the Cahora-Bassa dam.

Today, it is still with the reinvigoration of these two projects that the city counts on building its future.

With a population of just over 305,722, according to the 2017 census, the city of Tete has a relatively modest built heritage, consisting of half a dozen degraded colonial mansions by the river, and some buildings showing the spark of prosperity that characterised the last years of the colonial period, in an attempt to respond to the war situation.

Its most emblematic sights today are the Boroma Mission and the bridge over the Zambezi River.

By José Manuel Fernandes and João Paulo Borges Coelho

Source: HPIP

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.