Mozambique: Honey production helps families in national park buffer zone, keeps elephants away

Mozambique without reforestation program for charcoal production sector

DW / Charcoal sales station in Combomune, Gaza province, Mozambique

In Gaza, southern Mozambique, burning wood to make coal is destroying forests. Every year, 56,000 sacks of charcoal leave the Mabalane district alone, yet there are no programs to reforest the region.

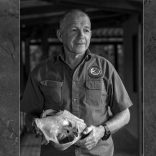

Gabriel Mugabe has been a charcoal producer for eight years. He knows that burning wood to make charcoal is bad for the environment, but this is his family’s livelihood. According to him, the business is not as profitable as one might think. A bag of charcoal sells for just 250 meticais, just over three euros. The profit margin is only 15 percent.

The 40-year-old charcoal burner knows that it is necessary to replace the trees he cuts down. “It is not just about being satisfied with the fact that we have benefited from cutting down trees. The government has to create conditions so that we can do this work – because it is for the good of our children.”

But Mr Mugabe acknowledges that he is not qualified for reforestation. “We need a lot of support where we operate. I alone, as an operator, cannot do anything without support, but if there is someone to come and teach us …”

It is in the Combomune Administrative Post, in Mabalane district, Gaza province, that most licensed charcoal associations and individuals such as Gabriel Mugabe operate. It is estimated that 56,000 bags of charcoal are produced each year in the district. But forests have fewer and fewer trees.

Authorities encourage reforestation but have no program

The District’s Economic Activities sector encourages forestry operators to replace the trees they fell, but does not have a reforestation program.

Narciso Cerveja, Director of Economic Activities in Mabalane, explains. “There are ideas. One concrete example is that of the Mabalane district, which does not have a reforestation nursery, but is supplied by the province. Only, in the last two years, due to severe drought, there are no plants there.”

“But I do not rule out the initiative, and encourage reforestation,” adds Cerveja. The district, he says, is interested in planting fruit trees, but not in replacing the native Xanasi trees most used for the production of charcoal.

The authorities justify the choice with the difficulty of reproducing this type of tree and the long time they take to grow – which raises questions about the future of the charcoal burners.

Prohibition triggers pressure elsewhere

Three years ago, to halt rampant deforestation, authorities banned charcoal production in the Chókwè and Massingir districts of Gaza province. But that only increased the pressure in other districts where production used to be carried out for domestic purposes only, says Júlia Mwito, provincial director of Land, Environment and Rural Development.

“There was migration here which intensified the production of charcoal. I am talking about Mabalane, Chigubo and Chicualacuala,” Mwito says. “We are in an overexploitation situation – charcoal extraction alone is twice the average in the province. It is worrying and it requires urgent measures.”

The provincial director says that it is necessary to increase environmental education in communities. Between single individuals and concessions, about 350 charcoal burners are licensed in Gaza province.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.