Mozambican population may reach 60 million in the next three decades - AIM

Mozambique: IMF forcing wage cuts; graphite part of US-China conflict – By Joseph Hanlon

In this issue

Economic

- IMF promises big wage cuts

- Interest rates up 2%

- Graphite’s role in US-China battle

- Maputo bus rapid transit cut again

Cabo Delgado 5th anniversary

- Police admit this is a peasant war

- Displaced up 20%, but some return home

- Will work on the gas resume?

- Government promised IMF big wage and staff cuts

The government promised the IMF big wage and staff cuts in order to gain IMF approval in May of a $456 mn Extended Credit Facility. The total civil service wage bill is to be cut by 17% by 2026, a cut of $425 mn per year from a peak in 2023. Staff cuts will be achieved “by replacing only one in three civil servants leaving the civil service, except in education, health, justice and agriculture.”

The IMF has always been obsessed with cutting the wage bill, but has never succeeded. And the new salary table will add $300 mn to the wage bill by 2023, mainly to the better paid. But large cuts must come in the three years after that.

Except for that, the IMF has largely accepted promises made before, such as a reduction in credit to state companies and more transparency. Government promises a reform of the Public Probity Law including improving the definition of conflicts of interest, requiring new public servants to submit declarations of financial interests when they are hired, and establishing public procedures for reporting conflicts of interest. Interestingly there are no requirements for transparency here, so the IMF will allow declarations of assets and interests to remain secret.

Similarly repeated is a promises to strengthen transparency in the management of Mozambique’s natural resources as part of reporting to the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Government promises to “reduce the scope for corruption and conflicts of interest in the natural resources sector.”

As before there is a promise to improve tax collection and to pay its bills on time. Government has promised to reduce the number of VAT exemptions. It announced that VAT would be cut from 17% to 16%, but that private health, private education, and rent for commercial and industrial premises would be subject to VAT. (Carta de Moçambique 23 Sep)

Many details of what is known as an “article IV consultation” remain secret. But on 14 September the Ministry of Economy and Finance released the key Political and Economic Memorandum – a government document with the commitments to the IMF. The Memorandum is on: https://www.mef.gov.mz/index.php/publicacoes/politicas/memorandos-de-entendimento-1/fmi/1705-memorando-de-politicas-economicas-gdm-fmi-2022-2024 We used those promises to estimate the wage and staff cuts.

(How we estimated wage cuts: Commitments in the memorandum are based on percentage of GDP rather than monetary amounts. World Bank says 2021 GDP was $16.1 bn. IMF predicts 3.8% per year GDP growth. The cost of the new salary scale in reported in Meticias. We assume a constant exchange rate of $1 = MT 64. Taking that together we estimate for 2021 a wage bill of $2.2 bn at 13.8% of GDP. Government promises no wage rise this year and the extra cost of the new salary scale is given in the Memorandum as $300 mn per year from 2023. So we estimate the 2023 wage bill at $2.5 bn, 14.5% of GDP. The memorandum requires wages in 2026 to be 10.8% of GDP, which we estimate to be $2.1 bn, down $430 mn (17%) from 2023. Jh)

- Interest rates up 2%; aid down, borrowing up

The base interest rate was raised from 15.25% to 17.25% by the Bank of Mozambique (BdM) on 30 September. The Association of Mozambican Banks (AMB) said it would maintain the prime rate, the interest charged by banks to good customers, at 20.6%. (O Pais 7 Oct) Compared to an inflation rate of 12.1%, this gives the banks a profit of 8.5%, and makes borrowing too expensive for most businesses.

External funding, mostly aid, fell by 12% in the first half of the year, from $187 mn in the first half of 2021 to $166 mn in the first half of this year. Government has increasingly resorted to domestic borrowing, which has almost doubled in less than three year, from $2.1 bn at the end of 2019 to $4.1 bn in September 2022. Government is now paying 19.63% on two year bonds, and in general banks are more willing to lend to government, which cuts credit to the economy.

International reserves have fallen sharply. They are now $2.7 bn, which would cover only 3 months of imports of goods and services, excluding the big projects, compared to August 2020 when they were $3.9 bn covering six months of imports.

Mozambique remains an extractive economy. The five biggest exports in the second quarter of 2022 were coal ($817 mn), aluminium (£597 mn), electricity ($129 mn), natural gas ($98 mn) and heavy sands ($94 mn). (Banco de Moçambique, Conjuntura económica e perspectivas de inflaçao, September 2022, 3 October)

- Mozambican graphite has a place in the US-China battle

Africa and Mozambique are part of a growing confrontation between the US and China. Mozambique was one of five African countries invited to the United States convened Minerals Security Partnership (MSP) which US Secretary of State Antony Blinken opened on 22 September in New York on the margins of the United Nations General Assembly High-Level Week.

The MSP is part of the US attempt to control critical minerals for the clean energy transition, many of which are now mainly produced in China. Blinken in particular cited the graphite mine in Balama, Mozambique. “Graphite from this mine will soon be sent for further processing to a plant in Louisiana, where it will create more jobs and where it will provide graphite used for batteries by American electric vehicle companies.”

The US Department of Energy (DoE) in an 18 April statement said “today the United States is 100% reliant on imported graphite as China produces nearly all of the high-purity graphite needed to make lithium-ion batteries.”

The DoE is providing $107 mn loan to the Australian owners of Balama, Syrah Resources, to build a processing factory in Vidalia, Louisiana, to produce graphite-based anodes for lithium-ion batteries. The DoE said the plant would create “98 good-paying, highly skilled operations jobs within the clean energy sector.”

Yet again, Mozambique gets nothing but a hole in the ground, while the manufacturing is in the US. For a critical mineral such as graphite, which the US wants from a non-Chinese source, Mozambique could have demanded that the processing be in Cabo Delgado. But it did not.

But on the same day Blinken spoke, workers at the Balama graphite mine were on strike, as were 100 workers at the nearby Ancuabe graphite mine, demanding wage increases. (Carta de Moçambique 29 Sept) Work at both mines was halted. Miners claim they are being paid less than the mining minimum wage of $162 per month.

At Balama, Local workers first went on strike on 7 September, calling for wage parity with employees brought in from elsewhere, and for benefits such as health insurance. Zitamar (22 Sept) notes that “the management of the graphite mine, is largely made up of Mozambicans from outside the region, who were evacuated at the start of this week [19 Sept] for fear that protests could turn ugly.”

And there are warnings that as more people are displaced by the new graphite mines, this could fuel the insurgency, as happened with people evicted from the ruby mines and gas project.

China is cutting back on lending to Africa, which means that “developing countries in Africa are losing a champion that for years allowed them to borrow at cheaper rates than they could find in capital markets.” (Bloomberg 7 Oct) China has been particularly important because it lends for long term infrastructure projects such as the Maputo ring road, that could not be funded elsewhere, and funding was without the conditions imposed by the IMF and World Bank.

- Maputo Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) cancelled again

Maputo Mayor Eneas Comiche on 30 September cancelled the long-awaited bus rapid transit (BRT), just a month after the World Bank said it would fund the project with $250 mn.

Widely used in Latin American cities like Mexico City and Rio, BRTs operate with reserved lanes and high platforms for easy boarding, and provide fast public transport (see photo). Johannesburg also operates a BRT system, and it seems ideal for Maputo.

First agreed with Brazil in 2014, the project has halted by the “lava jato” corruption scandal there, even though this project was not involved. The project was revived by World Bank director in Maputo, Idah Z. Pswarayi-Riddihough, but then trashed by the mayor. (Evidencias, 4 Oct, Radio Moçambique)

- A campaign to free the Xai Xai MDM head has been launched

In the 2018 municipal elections Agnaldo Navalha was head of the list for the Mozambique Democratic Movement (MDM) and thus a candidate to be mayor of Xai Xai, Gaza. He was convicted of being part of a demonstration on 4 or 6 February 2022 (prosecution reports differ on the date) and convicted of a crime his supporters say never happened. He is now in the Machava maximum security prison. (Ponto por Ponto 6 Oct)

- Cabo Delgado, after five years of war

This week was the fifth anniversary of the war, which formally started on 5 October 2017 with attacks on Mocimboa da Praia and Oasse. So far, 4,318 people have died in the war.

- Police commander admits this is a peasant war

When insurgents come into our fields, we must chase them with what we have – knives and machetes, Police Commander Bernardino Rafael told a meeting in Bilibiza, Quissanga district.

Rafael was telling peasants not to flee when attacked, because both sides are armed only with farm tools. The machete and the hoe are the two farm tools every peasant has. The machete is used for cutting everything – killing animals, clearing bush, pruning plants and trees, and countless other tasks, as well as chopping food, splitting open coconuts and other household tasks. Children learn to use machetes at an early age.

Much has been made of the insurgents frightening people by using machetes to cut off heads and arms. Indeed, common reports are that insurgent groups have only one or two guns and everyone else is armed with a machete. Rafael is rightly telling peasants that insurgents are mainly armed with the same farm tools that local peasants have.

Indeed, machetes are so common in war and peace that the Angola flag features a machete. The machete is called a catana in Mozambique, and the word panga is also used.

- Displaced up 20% this year, but some returning home

The number of displaced people in Cabo Delgado jumped 20% in the first half of this year to reach 946,508 said UNHCR spokesperson Matthew Saltmarsh in Geneva (04 October).

IOM (UN Migration) estimates in the period 1 June-27 September another 75,062 people were displaced for the first time. This includes 12,000 people fleeing four attacks by armed groups in September in Nampula, Saltmarsh said. But Alberto Armando, from the National Institute for Disaster Risk Management and Reduction in Nampula, said on 3 October that 47,000 people in the province fled during the attacks. Most have already returned home, Armando added, while 18,000 people are still displaced.

IOM also shows people returning. In the period 1-20 September, 3,410 displaced people returned home, including 2,837 to Mocimboa da Praia and 86 within Palma. Government estimates that 9000 people have returned to Mocimboa da Praia, enough to put under pressure the local health services still working from makeshift buildings. (AIM 27 Sep)

On 27 September, Rwanda force commander Major General Eugene Nkubito said more than 130,000 displaced people have now returned to their homes and villages. (Cabo Ligado 114, 4 Oct)

UNHCR estimates that there were 53.2 mn internally displaced people in the world at the end of 2021, so Cabo Delgado represents about 2% of the global total. Thus Mozambique is competing with Ukraine and other wars for attention

UNICEF has only received $16 mn toward is $99 mn budget for Mozambique, the agency said on 23 September. It has been able to add $14 mn of past unspent funds and $12 mn from core funds. But that only covers one-third of the needs caused by the war and cyclones Gombe and Ana.

And Unicef warns that the Cabo Delgado insurgency means that “seven districts were classified as entirely or partially hard-to-reach, with approximately 302,000 Internally Displaced Persons estimated to be in hard-to-reach locations across the province”.

- Fighting continues

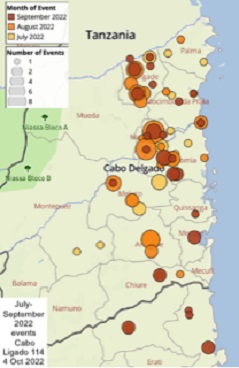

But the war continues, as the map below of incidents in the past three months shows.

Rwandan troops control Palma and Mocimboa da Praia districts, and that map shows that although the number of incidents is lower than in neighbouring districts, there are still attacks and Rwandan controlled areas are not yet secure.

The most serious fighting is in Nangade district on the Tanzanian border, and on the N380 main road in Macomia and Meloco districts. September also saw attacks and incidents is zones that had been considered safe – Quissanga and Metuge districts near Pemba, and south through Chiure into north-eastern Nampula province.

- Will work on the gas resume?

Mozambique’s Finance Minister Max Tonela is “very optimistic” that TotalEnergies will make a decision by March to resume work on its $20 billion liquefied natural gas (LNG) export project. “What Total has required is a long-term security assurance” and the government thinks the necessary conditions are in place, Tonela said in a Sept. 16 interview in Maputo. But Tonela is “not so optimistic” that ExxonMobil will reach a long-awaited final investment decision in the near-term. Exxon has a larger gas field further off shore adjoining Total’s. Exxon is revising plans for that project, including to allow for possible carbon capture and storage. Asked if he expected a final decision on Exxon next year, Tonela said: “It’s not easy to assume.” (Bloomberg 20 Sep)

“The energy crisis in Europe may lead TotalEnergies to return before peace is established in Cabo Delgado,” concludes CIP (Public Integrity Centre) in a 21 September report. https://www.cipmoz.org/pt/2022/09/21/crise-energetica-na-europa-pode-levar-a-totalenergies-a-regressar-antes-do-estabelecimento-da-paz-em-cabo-delgado/ Rising gas prices and gas shortages in France will increase the pressure on TotalEnergies. (Al Jazeera 24 Sep)

But TotalEnergies is looking elsewhere and has signed two contracts with Qatar to participate in the North Field South and North Field East, with investments of at least $3.5 bn, so it may not need Mozambique. Qatargas is already the world’s largest LNG producing company.

- Comment Caught between the climate emergency and other northern agendas

Mozambique will gain more support to exploit its gas as attitudes in both the global north and south change. The OECD on 29 July issued a study showing that rich countries broke their main climate promise to developing nations. In 2009, high-income countries pledged to deliver $100 billion a year by 2020 to help poorer countries reduce emissions and prepare for the effects of global warming, and they still have not reached that target. In 2015 all UN member states agreed the Sustainable Development Goals, but money has not been forthcoming. Also in 2015 at COP 21 it was agreed to keep global warming below 1.5ºC, but despite continued lip-service, the targets have been weakened in practice and further weakened by the Ukraine crisis. The new, unspoken target, is 2ºC, which will cause worse cyclones and droughts in Mozambique. The contribution of the global south to global heating is small, and the rich countries are content to further raise the temperature. So climate emergency considerations no longer carry much weight in the south.

“Fossil fuels are a killer but I can tell you that hunger kills faster”, said South African Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe on 4 October. Mantashe is pushing coal, the most damaging of fossil fuels. “We have seen the increase of coal purchasing from us to EU growing eightfold, 780%. As they take our coal, they at the same time tell us to move out of it quickly.” (News 24, 4 Oct) Despite ever more strident climate warnings, coal use is set to rise 0.7% this year to eight billion tons, the record level it reached almost a decade ago, according to the International Energy Agency. (Bloomberg 3 Oct)

Mantashe’s comment comes as part of tough negotiations with the north over the landmark $8.5 billion deal to help wean South Africa off its dependence on coal for more than 80% of its power. The deal was unveiled at COP-26 climate talks in Glasgow last year, without details. The rich countries – the US, UK, France, Germany and the EU – are offering high interest loans instead of the grants and low interest loans expected. And the lenders want to restrict the money to closing coal-fired power stations and replacing them with conventional renewable energy, as well as expanding the grid. South Africa wants to use some of the money to make the leap to green hydrogen, a technology now controlled by the rich countries and China, but the lenders are resisting. (Bloomberg 3 Oct https://furtherafrica.com/2022/10/07/south-africas-landmark-us8-5b-climate-finance-deal-hangs-in-the-balance/ )

The attitude in the south appears to be hardening. If the polluting north is going to raise the temperature and not pay the costs, then the south must be able to use its energy resources. This, of course has the backing of the oil and gas industry. The oil and gas industry has delivered $2.8bn (£2.3bn) a day in pure profit for the last 50 years, “providing the power to buy every politician, every system and delay action on the climate crisis”, according to the Guardian (1 July https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/jul/21/revealed-oil-sectors-staggering-profits-last-50-years).

- And a quote: Choiceless democracies enforcing IMF austerity

“Many of us on the continent began to refer to the phenomenon of Africa’s ‘choiceless democracies’ in the late 1990s. These are elected governments that come into office but have absolutely no possibility to alter the established economic and social policy framework that has been put in place to conform with the demands of a global neoliberalism overseen by the IMF and World Bank. Once these governments come into power, despite their planned economic and social development agenda, they find that they are required to use their legitimacy to enforce austerity and deflation. Effectively problems of poverty and inequality that have been structural to Africa’s development experience for decades simply got worse under the watch of the elected government and began to produce the disaffection that in a lot of cases has produced discontent.”

“Once in office, most elected governments in Africa quickly find that the rules are set already and economic policy-making is taken out of the domain of politics for the sake of ‘rationality’ and ‘predictability’ and all of the things that the World Bank and the IMF used to sell in their structural adjustment package. Therefore, politics is reduced to essentially a beauty contest around very inconsequential issues, a game of personalities and prejudices peddled by politicians. It should not be so-called rational economics that determines the frame, content, and the form of politics. Rather, it should be the issues which citizens aspire for and agree to buy into in terms of a national vision that should be the basis around which we construct economic policy.”

Adebayo Olukoshi, Distinguished Professor at the Wits School of Governance of the University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. “The process of democratic deceleration in Africa has been accompanied by a complex of discontents”. https://bit.ly/Olukoshi-democratic-deceleration

By Joseph Hanlon

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.