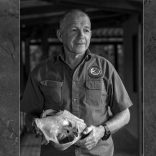

Mozambique: Marc Stalmans, renowned ecologist and Director of Science at Gorongosa National Park, ...

Mozambique films world’s last sanctuary for sharks, rays

Photo: Lusa

The sun has just risen, and several dolphins accompany the boat: they are escorting the expedition that soon goes to sea in Ponta do Ouro, Mozambique, with three marine researchers, loaded with equipment.

But this expedition is not even dedicated to dolphins, which jump and dive as a bonus before the main film, which will be recorded today under the sea.

There is a hidden world beneath the waves to which humanity is interconnected.

What sharks and rays inhabit this underwater world? – is the question that Jorge, Stela and Delson want to answer with several cameras to evaluate the health of one of the last strongholds of the planet where these endangered species still manage to thrive and that it is, therefore, essential to preserve.

Standing in the middle of the boat and with arms open, they take the metallic structures, rectangular skeletons with two video cameras (one on each end) that are thrown into the water with a rope up to a depth of 20 metres, a few kilometres from the shore.

Signalled with a buoy, they will film 60 minutes of life on the bottom of the southwest Indian Ocean, an area of the Earth where there are 225 species of sharks and rays, at least 36% of which are threatened by overfishing, coastal development, habitat loss and climate change.

The team launches four structures at four different points (eight cameras in action), delimiting the first filming area of the day, each structure with a ‘bait’, a bag with pieces of fresh horse mackerel on a rod to attract the neighbourhood in front of the cameras.

This is why this technique is referred to in the industry by the English acronym BRUV: ‘baited remote underwater video’.

Jorge Sitoe, 35, and Delson Vutane, 27, are assistants in a programme of the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), a partner of the Government of Mozambique in several initiatives, including this action of monitoring sharks and rays since 2018.

It is necessary to identify what type of shark or ray is present (or absent) and monitor their population, know whether they thrive or are in decline and why – for example, assessing whether it is necessary to prevent pollution or control fisheries, their implements and seasonality to never happen in the breeding season.

Hammerhead sharks have slow growth, late maturity and low reproductive capacity: pregnant females and juvenile elements are often caught in Mozambique, either as targets for the international fin trade or as collateral damage to tuna or other species fisheries.

It’s a problem because all sharks are a key species that maintain fish stocks, explains Stela Fernando, 38, a researcher at the Mozambican Oceanographic Institute.

They are “top predators”, from which only the healthiest elements escape, thus strengthening the “diversity and abundance of species in an ecosystem” that humanity uses as food or a tourist resource, for example.

If the population of any species changes, there are imbalances in the ecosystem and those resources are put at risk, as already seems to be happening on the northern coast of the country and others further up the country (like Tanzania and Kenya).

“We want to protect biodiversity because it has a role not only for ecosystems but also for us as human beings: it’s a win-win,” describes Stela.

In Mozambique, there are sharks and rays caught for export. Others are the attraction of divers coming from different parts of the world, and others are still protected, given their rarity on a planetary level.

But for this management to happen, it is necessary to know where to do it and identify them.

Jorge recalls that “formerly there was only one protected species” in the country, the white shark, but now “there are 14 species of sharks and rays protected in Mozambique, a considerable number”, he considers.

He says it is the result of “continuous work” that comes “because of these researches with the Government”, investigations at sea that serve to “support the best biodiversity management decisions”.

The work of these teams continues on land, for example, accompanying the arrival of fishermen, publicising new laws and helping them to identify what they’re carrying in their nets, and protecting the species that must return to the water to maintain the balance of the underwater world – without which, not even the fishermen themselves will have a future.

After an hour, Jorge and Delson give a hand: they pull the ropes, the cameras are hoisted, the material checked, and the bait bag replenished.

“Once, a huge grouper took all the bait,” Jorge recalls.

“Yes, a grouper, it wasn’t a shark,” which may even have a reputation for being violent, but the truth is that there have been no recorded incidents since 2016 in Mozambique, he says, living up to the phrase on one of the joint Government and WCS ‘posters’: “The sharks need our help”.

At the side, Stela records the numbers on the memory cards that correspond to each location before closing them in a waterproof box.

The boat moves on to another stop where another 60 minutes of underwater life will be filmed, with the team making six stops along 12 kilometres of coastline.

And at the end of the day, there are plenty of images to see to understand where the nooks and crannies are, what species are absent or present, what quantities of each species and how big each animal is.

Jorge takes a preliminary look. Then the images are sent to South Africa for analysis with a computer application that synchronises the films from the cameras and helps identify the animals.

Later in the day, the Mozambican team prepares to return to land in a country with the Indian Ocean as its main companion – 2,700 kilometres of coastline – capable of seducing young people like Delson for a professional future.

“It all starts at school”, he emphasises, on a path that, like his, includes “universities that also exist in Mozambique”, complementing a passion.

Research work like the one he is developing at sea requires “patience and a lot of control” to be sure that “nothing is being damaged down there” since the impact of man above is enough.

“Inspiring change” is the watchword for WCS, says Hugo Costa, director of the marine programme in Mozambique: the increase in the list of protected species is already visible, and more results will come through plans and strategies to guide actions on the ground.

For example, training will soon begin for authorities to identify shark and ray parts (such as fins, highly coveted in Asian markets) and thus be able to detect illegal trafficking networks and intervene.

“Reconciling economic development and biodiversity” is the guiding principle of WCS’s memoranda with the Mozambican government.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.