Mozambique: President of the Republic encourages expansion of World Vision's actions

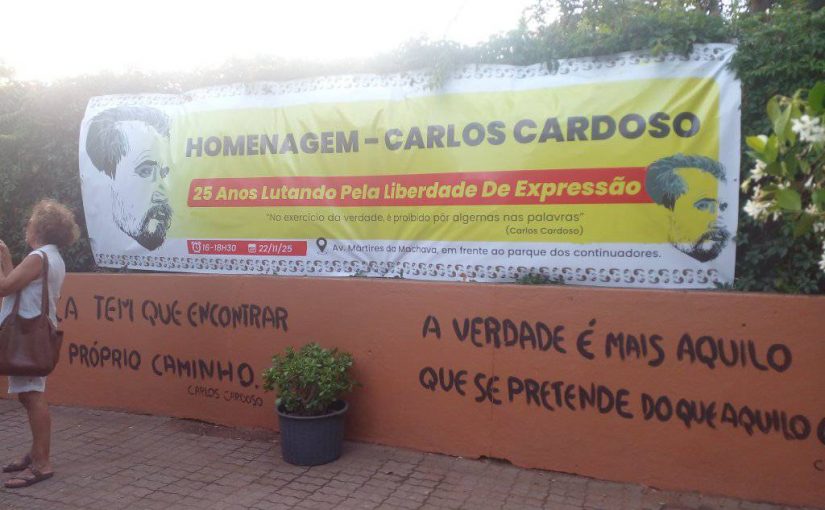

Mozambique: 25 years ago, on 22 November 2000, the most powerful voice in Mozambican independent media, that of Carlos Cardoso, was silenced for ever. – By Paul Fauvet

Image: Paul Fauvet/Facebook

25 years ago, on 22 November 2000, the most powerful voice in Mozambican independent media, that of Carlos Cardoso, was silenced for ever.

Cardoso was going home from the office of the independent newssheet he had founded, “Metical”, when his car was ambushed in front of Maputo’s main athletics stadium. His car was forced to a halt, and a hail of bullets rang out from an AK-47 assault rifle. One bullet struck his driver, Carlos Manjate, in the head, severely injuring him.

But Manjate was not the main target. At least five bullets struck Carlos Cardoso in the head, neck, chest and upper arm, killing him instantly.

As the news spread, a wave of shock and revulsion rippled through Mozambican society. Messages of condolence poured in from all over the world. Perhaps Cardoso’s friend, Teresa Lima, a Mozambican journalist then working on the BBC Portuguese service in London, summed up the feeling: “There is no coffin large enough for the heart of this man”, she wrote.

For over a quarter of a century, in a working life that coincided almost exactly with the life of Mozambique as an independent nation, Cardoso had come to embody all that was best in Mozambican journalism, all that was honest, questioning and combative. He was admired, respected and loved – even among some of those subjected to withering criticism in his paper.

All the key figures of state – the President of the Republic, the speaker of parliament, the president of the Supreme Court – attended Cardoso’s funeral on 24 November in Maputo City Hall. Addressing the mourners, President Joaquim Chissano said: “We were used to arguing with Cardoso. We argued with him because he raised pertinent questions that demand the attention of all of us. He forced us all to think. Today, when he is no longer with us, we can no longer argue. Who else will raise the questions with the force that he raised them?”

Giving the main funeral eulogy, the country’s best known writer, the novelist Mia Couto, declared: “We are not merely weeping for the death of a man. It wasn’t just Carlos Cardoso who died. They didn’t just kill a Mozambican journalist. A piece of the country has died, a part of all of us”.

Initially, despite Chissano’s heartfelt words, the police investigation into the murder scarcely existed. A month after the murder, “Metical”’s patience snapped, and it revealed that the police case file on the murder was just four or five pages long “and nobody is taking the case seriously”.

But this was one crime that would not be forgotten. Regular candlelight vigils were held at the murder site. The matter was raised whenever Chissano or other government official travelled abroad. Prominent foreign writers, headed by the Nobel Laureate Gunter Grass, issued an appeal, demanding to know “Who killed Carlos Cardoso?”. On 2 February 2001, when she received the Index on Censorship’s prize for “Courage in Journalism”, awarded posthumously to Cardoso, his partner, Nina Berg, took the opportunity to attack the “non-investigation” into her husband’s death,

But under public pressure, and because some honest police officers took their job seriously, the first arrests were made in February. The police tracked down the man who had driven the Citi-Golf used in the murder.

It turned out that this man, Anibal Antonio dos Santos Junior (better known as “Anibalzinho”) was well-known as a trafficker in luxury vehicles, with excellent contacts among high-ranking police officers. No doubt this explained why he had never been arrested before – even though a warrant for his arrest had been issued in 1991.

Anibalzinho recruited the other two members of the death squad – the lookout, Manuel Fernandes, and the man who fired the fatal shots, Carlitos Rachid Cassamo.

The investigation showed that the assassins had been working for the men who had defrauded the country’s main commercial bank, the BCM, of the equivalent of 14 million US dollars on the eve of its privatisation.

Vicente Ramaya, manager of the BCM branch in the up-market Maputo suburb of Sommerschield, allowed several members of the Abdul Satar family to open accounts. Within a few months those accounts were used to drain billions of meticais (millions of dollars) from the bank.

The mechanism of the fraud was simple. Dud cheques were deposited, and Ramaya allowed them to be treated as good cheques. The Satars were then able to withdraw, from other BCM branches, perfectly real money. When the fraud was detected, some members of the Satar family fled the country, but others stayed. Ramaya lost his job, but set himself up as a consultant.

The investigation ground to a halt because some of the attorneys and police involved were believed to be on the Satars’ payroll.

The fraud might have been forgotten had it not been for the determination of the BCM’s lawyer, Albano Slva, and the growing sense of outrage felt by Cardoso. For it was not the new owners of the BCM who lost the money: it was the Mozambican taxpayer, since the government felt obliged to replace the lost money before privatisation.

Cardoso was revolted at the way the state handled the matter. The BCM case “shows the degree of corruption we have reached”, he wrote. “14 million dollars are stolen from a bank, and the government replaces all the money. The matter becomes more repugnant as we watch the government fold its arms. Neither prosecutors, nor courts, nor the president are putting any pressure on the Attorney-General’s Office (PGR). Complicity in the theft is generalised”.

Silva and Cardoso were convinced that senior prosecutors, up to and including Attorney-General Antono Namburete, were involved in the fraud.

The pressure on Namburete was such that he yielded and ordered an inquiry into the behaviour of the prosecutors who had supposedly investigated the BCM case. The inquiry confirmed that the case file had been deliberately disorganised.

The credibility of the PGR had collapsed. Chissano stepped in on 3 July to sack Namburete and all six assistant attorney-generals. In retrospect this can be seen as one of the highest points in Cardoso’s career: he had played a key role in bringing down the whole corrupt and complacent structure of the Attorney-General’s Office, opening the path to rebuilding a credible legal system. But this also earned him implacable enemies who blamed him for the disappearance of their shield of impunity

Six men were charged with Cardoso’s murder – Ramaya, Ayob Abdul Satar and his brother Nini Satar, and the three members of the death squad. In the trial, that ran from November 2002 to January 2003, all six received long prison sentences.

Subsequently, those who ordered the murder have died – released on parole, Ramaya was shot dead in Maputo, while Ayob Satar was allowed to leave the country, but was gunned down in the Pakistani city of Karachi. Nini Satar was found dead, apparently of natural causes, in his Maputo prison cell.

By Paul Fauvet

Carlos Cardoso

10ago51-22nov00

Assassinado por ser jornalista e se recusar a que lhe colocassem ‘algemas nas palavras’. pic.twitter.com/PMbza9thsw— Sandra (@SandraDeMoz) November 22, 2025

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.