Xi Jinping holds talks with Mozambique’s Prime Minister in Beijing

Mozambique: Mediators’ governors proposal also calls for truce – Joseph Hanlon

Principles for provincial governance, drafted by the mediators and agreed by Renamo and government, were published yesterday (4 Nov) by Savana. They are billed as “orientations for legislative action by parliament”, and will be finally approved at the next negotiating session, expected 10 November. The mediators’ proposal (in Portuguese) is on http://bit.ly/2fnnGxS

The paper assumes that the constitution must be revised, and says that “once the principles that will guide the revision of the Constitution are agreed and delivered to Parliament, a truce will be declared.” This suggests, but does not say, that this is a separate document still to be written.

Truce, constitution, provisional governments

Although the word “truce” is in the title of the document, the final two paragraphs of the document contain three bombshells: truce, the need for a constitutional amendment, and Renamo provisional governments in the provinces. None are mentioned earlier in the document.

The final paragraph of the mediators’ proposal says: “Once the principles that will guide the revision of the Constitution are agreed and delivered to Parliament, a truce will be declared to allow discussion in a more favourable environment to resolve the issue of the provisional Renamo governments in the provinces. After reaching an agreement on this matter, as well as the other points provided for in the dialogue agenda, the truce shall be final, with a view to the ceasefire and the expected meeting at the highest level.”

Changing the constitution to elect governors probably requires a referendum, and there has never been a referendum in Mozambique. It had been widely assumed that a way would be found to get around the constitutional restriction, as was done with elections. The constitution says the President sets the election date, but the electoral law says parliament should choose two weeks in November and the President must pick a date within that period. There should be a similar solution for governors, for example that the provincial assembly picks a single candidate and asks the President to appoint that person. The mediators’ document also appears to assume that the constitutional issue must be dealt with in a separate document.

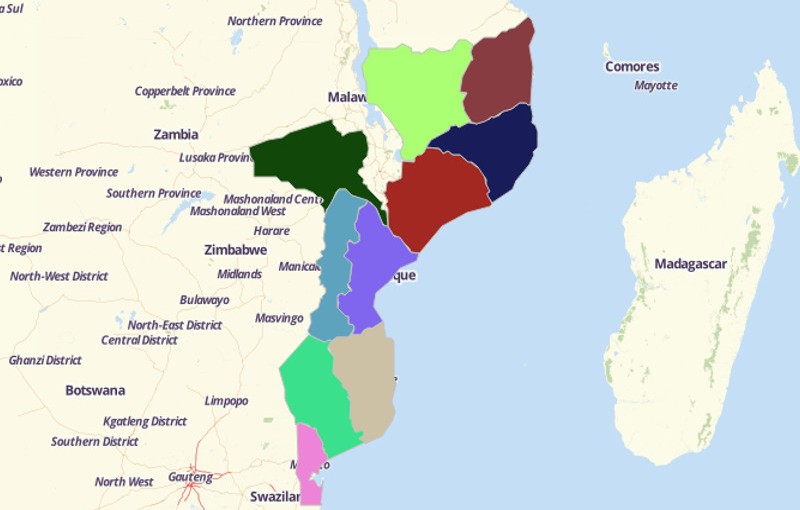

Finally the phrase “the issue of the provisional Renamo governments” links to Renamo’s demand to appoint governors in six provinces in the period before they are locally selected.

Governors and governance

The key point of the mediators’ proposal is that the provincial governor is to “chosen locally” (“excolhido localmente”) but the document does not say how this is to be done.

A second point of agreement is that district administrators would be chosen by the governor and approved by the provincial assembly, rather than being named by the national President.

The other main issue is how much power the province will have and how much power remains with the Mozambican President. At present the governor is named by the President and is subordinate to the President, but delegated powers are ill-defined and wide-ranging. Renamo wants the governor to retain these virtually dictatorial powers and be free to introduce alternative policies, while Frelimo will agree to a locally chosen governor only if powers are sharply restricted to be similar to those of elected municipal mayors. This mediators’ document leaves this wide gap and ensures extensive negotiation to come.

The negotiation is around a set of words. Is Mozambique a “unitary” state like France, or a “federal” state like Germany? A distinction is also made between “decentralization”, which involves some policy making power given to lower levels, and “deconcentration” which merely increases administrative autonomy at local level. The mediators touch all bases with this paragraph:

“The Republic of Mozambique is a unitary state, which respects in its organization the principles of deconcentration of power, territorial decentralization of public administration and local government autonomy. The autonomy of provinces does not affect the unity of the State and shall be exercised within the framework of the Constitution and the law.”

And it leaves the key decision for further negotiation: “It is for the law to define the relationship between the different levels of administration of the apparatus of the State. … The competencies of the provincial government and assemblies, the competencies of central government, and shared issues must be clearly set out. … It is up to Parliament to clearly establish the powers of elected bodies and representatives of the Central State Organs.”

The document indirectly takes into account Frelimo’s reluctance to decentralise power, even to elected Frelimo mayors. Even though the mayor of Maputo is elected, the President appoints a governor of Maputo city, to keep a check on the mayor; in other cities there are both elected mayors and nominated district administrators for the same cities. This is raised in a paragraph which says “The central state organs are ensured their representation at the various territorial levels, but without interfering with the duties and powers of the elected bodies.”

Provincial assemblies keep the present powers to approve and oversee the provincial plan and budget. But there are two new provisions: “Each provincial program shall include a project of reconciliation between peoples and political, economic and social entities, involving existing civil society institutions in the territory and at national level. Each provincial program must include measures for a credible fight against corruption.”

By: Joseph Hanlon

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.