Mozambique Elections: Frelimo calls on authorities to “clarify” double homicide

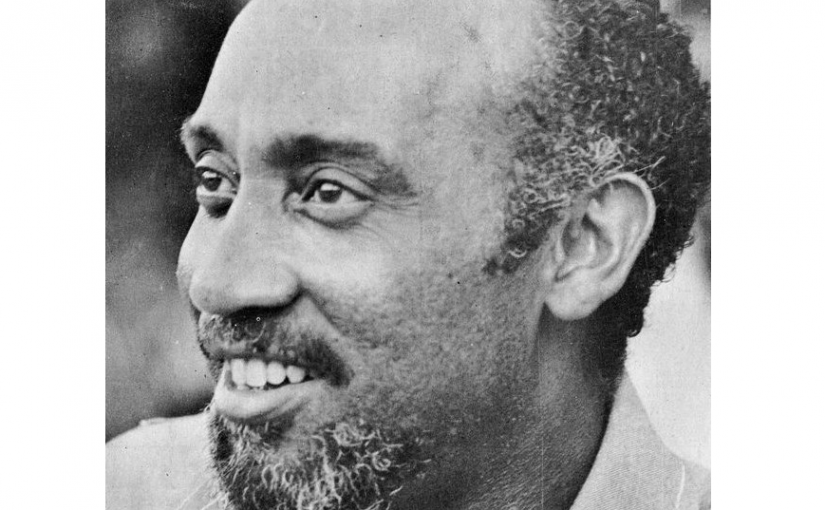

Just in: Mozambique’s Marcelino dos Santos, historic Frelimo leader, dies at 90

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Marcelino dos Santos, one of the founders of the Mozambique Liberation Front (Frelimo), passed away this Tuesday at the age of 90, President Filipe Nyusi has announced. The historic leader was also one of the symbols of African nationalism.

“We have lost our icon, Comrade Marcelino dos Santos,” Mozambican head of state Filipe Nyusi said on Tuesday (11/02) at the end of a rally in Pemba, Cabo Delgado province.

“We will organise ourselves, as a government, because he has already been proclaimed a national hero. We did not wait for what happened today to declare him our hero,” Nyusi declared.

Marcelino dos Santos, one of the symbols of African nationalism, was also a prominent figure in Mozambican politics – a “leader in the shadows” within Frelimo. One of his greatest contributions in post-independence was his prominent role in the building of the state. But he also faced questioning at some points in the country’s history.

Symbol of African nationalism

Born in Lumbo, Nampula province, Marcelino dos Santos does not belong to Mozambique alone. His role in building nationalism in Africa and the subsequent rise of liberation movements took his name across borders.

He was one of the founders of Frelimo, a united front of three movements. Frelimo was founded in Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika on 25 June 1962, when three regionally based nationalist organisations: the Mozambican African National Union (MANU), National Democratic Union of Mozambique (UDENAMO), and the National African Union of Independent Mozambique (UNAMI,) merged into one broad-based guerrilla movement.

Marcelino dos Santos served as Frelimo’s deputy president from 1969 to 1977, when the organisation was fighting Portuguese colonialism in Mozambique. Post-independence, he continued to hold prominent positions when Frelimo became a political party and took over the government of Mozambique.

“And he also imprinted something very important within Frelimo, which was respect for public things, respect for what belonged to the organisation, discipline, etc,” historian Yussuf Adam points outs.

The anti-leader leader

“As Aquino de Bragança used to say,” Adam notes, “Marcelino was never president of Frelimo. He had the functions he was given and performed them. But he had a great characteristic: he was the anti-leader leader. He was the one who managed to lead without being a formal chief, and that is something we really owe to Marcelino dos Santos.”

He wrote the first Frelimo statutes, and, shortly after independence, became Minister of Planning and Development. He was also president of the first Popular Assembly until 1994, the year in which Mozambique held its first elections.

But not everything went well. There are some episodes in the history of the party and of the country that have caused suspicion among his fellows.

“Marcelino was responsible for the Perspective Economic Indicative Plan, the grand plan to transform Mozambique into a socialist economy. But it is necessary to be careful with what I call public and private discourse, because Frelimo, in one way or another, for many years had a collective management and the decisions were taken collectively. In the private forum there may be some things that could be less favourable,” Adam says.

“My problem was never to be president”

As a nationalist, his deeds are more important than his failures, and in his homeland many people wondered why a strong figure like Marcelino dos Santos never became president. Without any evidence, it was conjectured that it was because he was of mixed race, and would therefore be associated with colonialism.

In an interview with Rádio Nacional de Angola in 2006, Marcelino dos Santos replied: “My problem was never that of being president. In fact, in Frelimo, we have a way of being, a way of conduct which still prevails today: we never decide what we want. I know that a lot has been said [of the possibility of Marcelino succeeding Samora Machel when he died in 1986], but the fact is that I did not. I don’t know [why I was not elected], go ask those who did not elect me. One day I will explain – I am preparing my memoirs and I will make reference to that – but let it be clear that what happened, happened correctly. The fact that I wasn’t president [of Frelimo] when Mondlane died, and the fact that I wasn’t president [of the Republic] when Samora died].”

In that interview, Marcelino dos Santos also quoted German playwright Bertolt Brecht: “Happy are the people who have no need for heroes”, which he interpreted as referring to a future time when there would be no need for a vanguard. But, today, that vanguard is still needed.

Given the contribution he made to his country, to Africa and the world, wasn’t he himself a hero to unhappy people?

“I have a big problem with this concept of hero,” dos Santos replies. “There was a great Mozambican poet who said that the hero is served dead. I would not want to talk about it, but I think he the hero is an example to be immolated in many things, and probably an element not to be immolated in others, but he is someone who made a political trajectory of so many years, endured Frelimo in the worst of the crisis and always assumed important roles with other people and several Frelimo teams that made the big transitions.”

Marcelino dos Santos – poet

His combat was not restricted to the political field; he also used writing in the struggle, under the names of Lilinho Micaia and Kalungano. “Canto do Amor Natural” was the only book published under his own name.

At the time when combat poetry was common, he published poems in ‘Brado Africano’ in Mozambique and in two anthologies published by the House of Students of the Empire in Portugal.

Marcelino dos Santos was born in 1929, son of Firmino dos Santos and Teresa Sabina dos Santos, and was raised in Lourenco Marques.

When he left Mozambique in 1947 to continue his education at the Industrial Institute in Lisbon, Portugal, he already showed himself ready to carry a torch held by his father’s generation. Firmino dos Santos, a member of the African Association of Mozambique, had urged revitalisation and unity among Mozambicans in their pursuit of justice and social equality. In a 1949 letter to the association from Lisbon, Marcelino similarly urged members to put aside individual considerations and stand united.

At the House for Students of the Empire in Lisbon, where colonial youths studying in Lisbon gathered in the late 1940s, dos Santos and others increasingly articulated their Africanist and nationalist sentiments through poetry and prose. Here dos Santos discreetly shared his ideals and aspirations with Amilcar Cabral, Agostinho Neto, and Eduardo Mondlane—men destined to become nationalist leaders in Guinea Bissau, Angola, and Mozambique, respectively.

By 1950, however, the political atmosphere in Lisbon was tense. Neto was arrested, Mondlane moved to study in the United States, and dos Santos and others relocated in Paris.

In Paris dos Santos lived among leftist African writers and artists affiliated with the literary journal Presence Africaine.

He published poetry under several pen names— Kalungano in Portuguese language publications and Lilinho Micaia in the collection of his poetry published in the Soviet Union. In the 1950s his skill as a nationalist strategist and mediator sharpened as he urged Portuguese political exiles in Paris to broaden their opposition to the Salazar regime in Portugal and embrace the nationalist cause.

The Anti-colonial Movement (MAC), formed in Paris in 1957, was in part a result of dos Santos’ work among this exile community. At the All-African Peoples Congress at Tunis in 1960 a broader alliance emerged incorporating the nationalist movements of Angola and Portuguese Guinea.

By 1961 nationalist groups proliferated, and all were galvanised by the outbreak of violence in Angola.

Dos Santos had joined the Paris branch of the National Democratic Union of Mozambique (UDENAMO), the first nationalist party formed largely among Mozambicans living in exile, but he continued to actively pursue solidarity at the international level.

At a meeting in Casablanca in April 1961 the Conference of Nationalist Organisations of the Portuguese Colonies (CONCOP) was formed. Dos Santos was elected permanent secretary charged with coordinating nationalist activity in an effort to force an immediate end to colonial rule. From CONCOP’s headquarters in Rabat dos Santos assumed his role of explaining the nationalist struggle to an international audience.

In 1962 Eduardo Mondlane assembled representatives of Mozambican nationalist groups in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, to attempt to forge a united front to undertake the struggle for independence, and dos Santos lent his support. The result was the foundation of the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (Frelimo). Frelimo, the party which undertook and waged the war for independence from Portugal, held its first congress in Tanzania in September 1962.

While continuing with CONCOP dos Santos increasingly turned his organisational and expository skills to sculpting Frelimo’s political and military goals.

By 1964, with the outbreak of the hostilities in northern Mozambique, dos Santos, as Frelimo’s secretary for external affairs, became one of the movement’s principal spokesmen.

His powerful presentations before the Organisation for African Unity, the Afro-Asian Solidarity Conference, and the United Nations helped win international recognition of the legitimacy of Frelimo’s petitions for political, military, and financial support.

With the tragic murder of Frelimo’s president, Eduardo Mondlane, dos Santos was elected to Frelimo’s temporary ruling triumvirate (dos Santos, Uria Simango, and Samora Moises Machel).

In 1970 he became vice president under Samora Machel—a position he held throughout the war for independence.

Working at Frelimo headquarters in Dar es Salaam and in the war zones, dos Santos focused on the key political aspects of the armed struggle. Using the bonds of friendship and the political skills he developed in the 1950s, he helped cement links of political cooperation throughout the war, during the difficult negotiations leading to the independence of Mozambique, and ultimately into the Herculean task of constituting a viable new nation.

When the Council of Ministers of the People’s Republic of Mozambique was sworn to office on July 1, 1975, dos Santos assumed the key positions of vice president of Frelimo and minister for development and economic planning. After independence he held a number of important positions within the government and remained active as a member of Frelimo’s Central Committee charged with political strategy. The challenge during the late 1970s and 1980s was to rebuild the country while defending Frelimo and the government from an armed takeover by the opposition group Renamo.

From 1981 to 1983 dos Santos left government office to concentrate on strengthening the party. He returned to office in 1983 as governor of the province of Sofala in central Mozambique, and in 1989 served as president of the People’s Assembly. During this time, he worked diligently to establish internal stability; some progress was finally achieved in October 1992 when a peace agreement was signed by Frelimo and Renamo.

Through the mid-1990s he continued as theoretician within Frelimo’s Central Committee, working to reform the country’s economic and political structures from within. The long war against Renamo had left the former Portuguese colony bankrupt, earning it the dubious distinction of the world’s poorest nation. Dos Santos often led delegations representing Mozambique at important international conferences, such as the Southern Africa-Cuba Solidarity Conference in May 1995.

His essential contributions were in the area of international relations, deftly aiding Mozambique in its determined posture of non-alignment, and in the development of Frelimo policy designed to develop socialist programs to serve Mozambique’s majority population.

Further Reading

There are no detailed biographies of Marcelino dos Santos, but some of his best speeches and poems are available in English. His “Address to the Sixth Pan-African Congress” in Africa Review (1974) and “The Voice of the Awakened Continent” in World Marxist Review (Prague, 1964) are exemplary. Lotus: Afro-Asian Writings has two articles which focus on Marcelino dos Santos as a poet and on his work in the context of nationalist poetry in Mozambique: Luis Bernardo Honwana, “The Role of Poetry in the Mozambican Revolution,” volume 8 (Cairo, 1971) and “Marcelino dos Santos,” volume 18 (Cairo, 1973). He is listed in Africa South of the Sahara (11th and 12th editions. London: Europa Publications, 1981, 1982. Biographies in ” Who’s Who in Africa South of the Sahara” section.) Periodicals and journals with additional information include: Africa Report (May-June 1989); African Communist (Third quarter 1995); and Current History (May 1993).

Three general works provide the necessary context to understand the historical contribution of Marcelino dos Santos. Allen and Barbara Isaacman’s book Mozambique: From Colonialism to Revolution, 1900-1982 considers both the role of protest poetry and Marcelino dos Santos’ contribution as poet and politician (1983). Eduardo Mondlane’s The Struggle for Mozambique, republished with an introduction by John Saul and a biographical sketch by Herbert Shore (London, 1983), is the classic work on the period. Finally, Barbara Cornwall’s The Bush Rebels: A Personal Account of Black Revolt in Africa (1972) adds a personal glimpse of dos Santos the man.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.