Mozambique: At least 45 homes burned down by alleged terrorists in Nampula province - government | ...

Joint Op-Ed from the British High Commission in Maputo and the Embassy of Ireland in Mozambique on the 25 years of the Belfast Good Friday Agreement

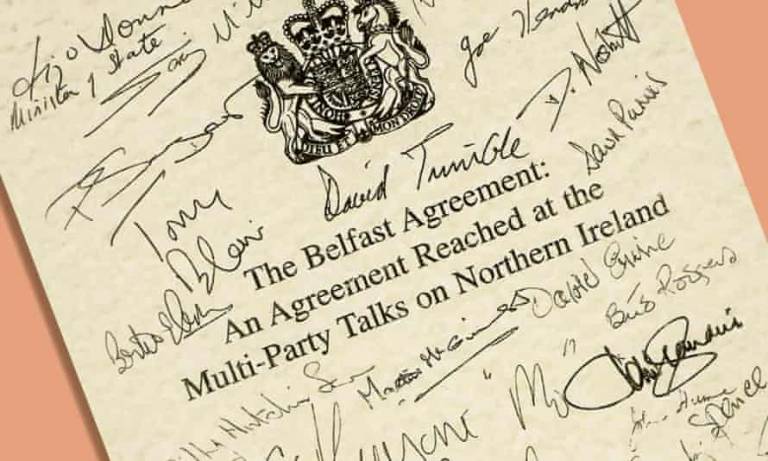

FILE - For illustration purposes only [ File photo: Whyte's auctions]

10 April marked the 25th anniversary of the 1998 Belfast or ‘Good Friday Agreement’ that brought an end to 30 years of conflict in Northern Ireland killing over 3,500 people, injuring and leaving thousands more deeply traumatized by violence. Reaching this point in the peace process marked the culmination of decades of negotiations, political leadership, vision, and compromise to break the cycle of violence that marred the island of Ireland for 30 years. This leadership with representatives from across the traditions of the island, from the two Governments (Ireland and United Kingdom), from international partners and friends, from civil society, and from ordinary citizens, insisted on a peaceful, democratic future. It transformed relationships at every level across these islands.

As Mozambique ends its first month long Presidency of the UN Security Council, it will be a good opportunity also to turn outwards to share lessons from its hard-won experience of making and building peace. This commonality is important and relevant.

In our roles as British High Commissioner and Ambassador of Ireland to Mozambique, we have the enormous privilege of forging connections between diverse peoples, countries, cultures and individuals. The political leadership that achieved peace in Northern Ireland in 1998, is well known for having been significantly influenced by South Africa’s transition. In 1997, separate planes and meeting rooms had to be organised for the different political parties in Northern Ireland to meet Nelson Mandela, where they heard the same point – you negotiate with your enemy, you have to talk to them, in the first instance to understand them.

We were lucky to have so many friends to Northern Ireland’s peace process. Senator George Mitchell and President Bill Clinton personally engaged in intensive mediation efforts and the EU provided over €1.5bn of support that was directed towards building relationships between communities involved in the conflict in Northern Ireland and Ireland. The list of those from outside of our islands who helped us on this journey is indeed lengthy. However, no history of these achievements could be complete without reference to South Africa’s now-President Cyril Ramaphosa, Finland’s President Martti Ahtisari, or Canada’s General John de Chastelain, whose role in the decommissioning of arms in Northern Ireland was crucial to the peace process and speaks to the global support underlying the island’s peace.

Peace was also possible because of agreement on some principles which have since inspired peace-making efforts around the world.

The Belfast Good Friday Agreement recognises the complexity of identity, and the right of the people of Northern Ireland to identify and be accepted as British, or Irish, or both. The Agreement also recognises the legitimacy of people having different aspirations for the future of Northern Ireland, and to pursue these in exclusively democratic and peaceful ways. The principle of consent in the context of the Belfast Good Friday Agreement means that Northern Ireland remains part of the UK and shall not cease to be so without the consent of the majority of the people of Northern Ireland. Parity of esteem between Northern Ireland’s traditions was another principle at the heart of the Agreement that has emphasised the importance of fair and equal treatment for all.

These core values created a new, finely judged balance that continues to underlie the process of peace and reconciliation today. As co-guarantors of the Agreement, our two Governments are under specific duties to protect this balance and uphold the Agreement.

Twenty-five years on, peace building is a continuing process. While we have made substantial progress, there is of course more to do to ensure that all the people of Northern Ireland fully enjoy everything made possible by the Belfast Good Friday Agreement. The Agreement acknowledges the need to “address the suffering of the victims of violence as a necessary element of reconciliation”. While our Governments may differ on how we approach to this important issue, we affirm the absolute importance of reconciliation.

The work of peace and reconciliation is an ongoing and shared commitment, as is seeing all parts of the Agreement implemented fully and effectively. Throughout, we have gained enormously from sharing our journey through academic, civil society, business and political networks. Reform to Northern Ireland’s policing service and the successful transfer of crime and justice matters to the Belfast Good Friday Agreement institutions in 2010, in particular, is often held up as a model for other post-conflict countries. International engagement has brought fresh perspectives and impetus to tackle the challenges that remain.

We wish Mozambique all the very best as it starts to share its stories of the past to shape the future.

History says don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up

And hope and history rhyme.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.