Mozambique mourns theatre icon Evaristo Abreu — beloved actor, director, and educator

J. Hewlett: Can You Smell the Rain? – Book review by Colin Waugh

This memoir of an African-raised farmer and businessman, tracing a career and life centred on Mozambique, for the English language reader represents a specially informative and readable chronicle of the past 30 or more years in the country’s history. At the same time it is an unapologetic autobiography of the author and his family’s lives across Africa, but anchored by a chain of experiences beginning in 1984 with his posting to the fledgling Marxist Mozambican state.

Academics with an interest in contemporary Mozambique may find the personal accounts of Hewlett’s family evolution and displacements of minor relevance, just as others may find it refreshing to read about familiar events and milestones in the country’s development through the optic of a businessman, rather than those of a historian, sociologist or political scientist. However, anything which lacks in methodological rigour is more than made up for by the vivid first-hand accounts of meetings with many of the decision makers and power brokers who shaped modern Mozambique.

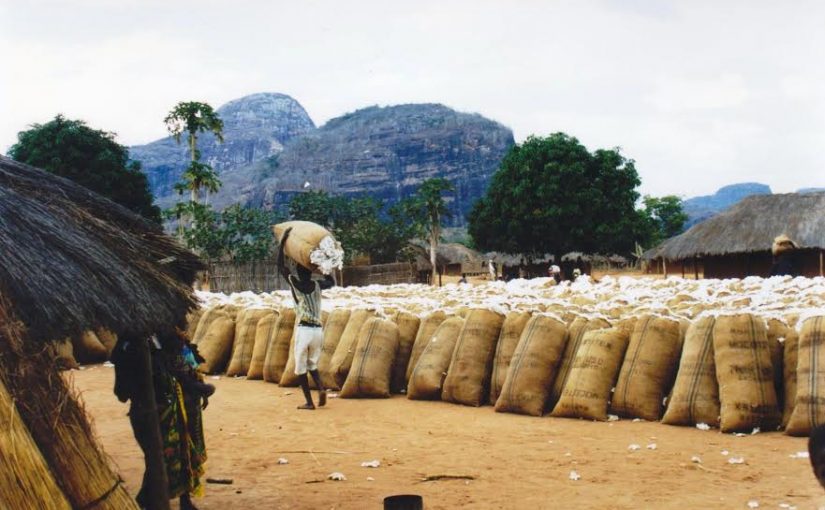

A fast-rising agri-business manager for Lonrho, the iconic Africa-centric UK multinational brought to prominence by its visionary and controversial chief executive ‘Tiny’ Rowland, in 1984 the author receives his first Mozambican assignment as head of the newly-formed LOMACO which sets out to plant and sell cotton grown in central Mozambique. With President Samora Machel’s blessing, LOMACO first receives the go-ahead to cultivate but then also successfully negotiates, through the veteran general Alberto Chipande, the right to raise and deploy a private militia formed of a 1400-plus mercenary-led force, to protect its operations from Renamo.

With an annual budget of over a million dollars the professional protection became unsustainable commercially in a volatile world cotton market. Other kick-start business operations were launched in the south of the country at Machel’s urging, aimed at reviving an agriculture sector devastated by war, drought and disastrous early Marxist experiments. Negotiating, financing and implementing these programmes bring Hewlett and Rowland into even closer contact with the Frelimo Government and further into the confidence of its leaders.

Soon the company that former British Prime Minister Edward Heath once described as exhibiting the ‘’unacceptable face of capitalism’’ was throwing a lifeline of food production and foreign exchange earnings to what had been an almost template Marxist African state.

A few years later, when Frelimo is finally persuaded that the war is unwinnable, Lonrho occupies a pivotal position as power broker having established regular contacts with Renamo’s leader Afonso Dhlakama from operating in territory under his forces’ control, as well as with Robert Mugabe, the South Africans who held Renamo’s purse strings and other leaders in the region eager to see a Mozambican peace agreement.

From there, the shuttle diplomacy begins from Maputo, Nairobi, Pretoria, Gaborone and ultimately Rome, with meetings between warring factions and peacemakers continually arranged and cancelled and with cease fire discussions agreed then broken off. Rowland by now more interested in his legacy as African peacemaker than global capitalist, and with the author frequently at his side, throws the weight of his charm, his connections and Lonrho’s considerable resources into the effort to bring the parties to sit down together. The list of personalities that Lonrho interfaces with reads like the ABCD of the August 1992 Rome Peace agreement. Ajello, Botha, Chissano and Dhlakama are all there, each with their own personality quirks and personal insecurities, each manoeuvring to the last minute (and often beyond) to secure what they need to come out of the deal in the strongest position.

John Hewlett’s presence at these encounters not only offers a first-hand glimpse of the dealmakers that finally agreed to end the civil war; there are also insights into the personalities that were to shape and reshape peacetime Mozambique. Thus we meet Frelimo chief negotiator and Minister of Transport Armando Guebuza, already hustling Lonrho for some insider shares in the booming business of the newly upgraded Cardoso Hotel – and learn the author’s opinion, perhaps naïve in retrospect, that Guebuza then seemed … ‘’as relaxed about the presence of whites in government’’ as did President Chissano.

Then during a dinner engagement in Maputo’s colourful Rua Bagamoyo, the reader is treated to a vignette of the future first lady delving into her handbag for some extra piri-piri to help liven up her husband’s Chinese food. It seems that eating out then, as during his presidency, no food was too hot, and no deal was too big, for the future two-term president.

Away from Mozambique during peacetime, John Hewlett’s career went through its own turbulent phase as following a change of chairman, in 1995 a boardroom coup led to the ouster of Tiny Rowland and his only supporter at the table, the author John Hewlett. Rowland walked out of Lonrho that day and Hewlett was not far behind him as the company entered a new phase in the low-commodity price environment of the mid-1990s. New management stripped off the mining assets into the Lonmin subsidiary while also creating Lonrho Africa for the rump holdings then set about dismantling much of the diverse portfolio of agricultural businesses that Hewlett’s mentor had built up.

Looking elsewhere for new challenges, Hewlett soon ends up on a plane to New York and enters discussions of a pan-continental fundraising assignment aimed at financing PepsiCola’s African expansion. But the engagement is short lived, and soon, turning full circle, the seasoned Africa cotton entrepreneur is back at what he liked best, working with farms in the Mozambique he by now thought of as home. Hewlett’s new Mozambique business, built around a core of the former Lonrho assets, went on to employ 100,000 small-scale farmers at its peak and accounted for over one-third of the country’s cotton production.

In a final career phase Hewlett and his wife Marjolaine withdraw to Pemba and the beautiful Quirimbas Archipelago off Cabo Delgado and plunge into marine conservation, then later launching a luxury resort project, which over time is crowned with success, counting elites and celebrities from around the globe among its guest list.

The twin themes of this short book, both personal and business are about challenge and survival in difficult circumstances, but amid the colourful tapestry of characters, business, political and family, there is an overlay of optimism about Mozambique throughout. There was indeed optimism about the political evolution of the country in those immediate post-Rome Accord days which was shared by those of us who were involved in helping to lay the early foundation stones of peace. We sensed renewal then and certainly hoped for better by now.

Thus, in the wake of Mozambique’s close-run second elections in 1999 and as Joaquim Chissano began his second term as president at the dawn of the new century, Hewlett was able to comment, that ‘’…democracy in Mozambique seemed to be taking hold.’’ Little could he have known that Mozambican democracy of the type which many hoped for then was probably already at its zenith in that year.

Hewlett reflects in closing how Africa has changed almost beyond recognition, especially in business and economics with the advent of new investment partners such as China, with very different ways of doing business than their western predecessors. He ends his memoir by noting that as outgoing president in 2004, Joaquim Chissano won the 2007 Mo Ibrahim prize for his achievements in African Leadership. It is also noteworthy that last year, Ibrahim held back the $5m leadership prize, considering that no current African leader, let alone a Mozambican one, was considered deserving of the award.

Maputo, April 2017

Colin Waugh

Can You Smell the Rain? : A Memoir of Mozambique: From Communism and War to Democracy and Peace – From Boardroom Intrigue to Private Islands – by John Hewlett

Paperback – 28 Feb 2017 – distributed by “Kapicua Lda” in Maputo and available at “Mabuko” in Av. Julius Nyerere.

In South Africa it is available from “Exclusive Books, “Bargain Books” and from the publishers at www.30degreessouth.co.za.

Also available on Amazon.com from June 2017.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.