Mozambique: MISA protests at harassment of journalists in Cabo Delgado - AIM

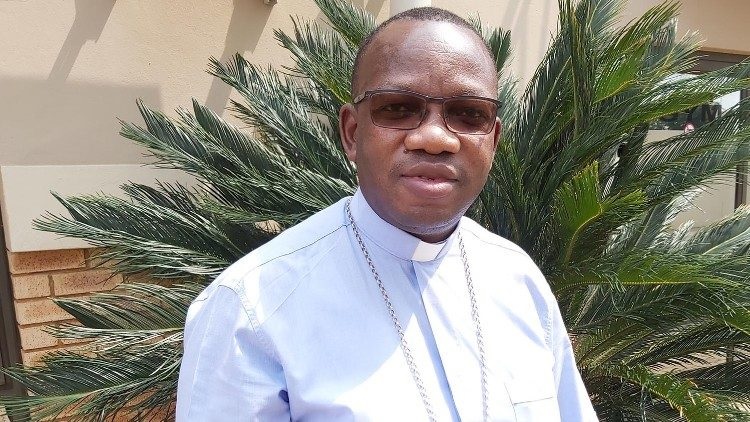

Interview with Dom Juliasse Sandramo, Apostolic Administrator of the Diocese of Pemba – Mozambique

- Interview conducted by Pedro Jorge Castro in Pemba, and published, in Portuguese, on 22 April 2021, by Observador.

Two months after taking over the diocese of Pemba in Cabo Delgado, and a few days after the Mozambican bishops signed a devastating statement, the new Bishop of Pemba [Apostolic Administrator], D. António Juliasse Sandramo, gave an interview to the Observador at his residence.

Also read: Cabo Delgado: “If I were afraid, I wouldn’t be a bishop” – Dom António Juliasse

Over the course of 45 minutes, he criticised the lack of action against corruption “that reaches the highest levels”, attacked the way the top of the regime tries to minimise the war in Cabo Delgado, and relayed the dramatic testimony of those who took up arms against insurgents in Palma, but were forced to flee.

A statement from the bishops of Mozambique has just been issued, stating that “there are no clear indications that the causes that fuel this conflict will soon be overcome” in Cabo Delgado. What should the Mozambican government be doing, that it is not ?

The bishops noted the social context in the country. What should be done is to mobilise energies and efforts, collectively, to discover safe paths and the integration of the youth and all the people.

Isn’t that being done?

The bishops understand that it is not being done properly. If you ask a young person which way the country is going, there is great dissatisfaction. If we ask what their future is, they find it difficult to comment on it. In our view, paths must be clearly pointed out – which way we are going. When you see that a few are benefiting more and more and so many other young people have no opportunity, do not discover any opportunities, they are vulnerable to any type of thing.

The communiqué refers to the total lack of transparency in the extraction of resources and states that young people are victims of a culture of corruption. In the church’s view, is the regime generally corrupt?

This is not to hide – everybody knows. Several presidents of Mozambique have promised to fight corruption in a forceful way. Instead of fighting, things got worse and worse. Everyone understands this – the disease has been diagnosed for a long time. But there is no effective fight. It is very difficult to fight oneself. How can a corrupt man fight against himself? It takes a kind of revolution. Corruption has become a normal thing. To get a job, you have to pay a lot of money. A young person who has just left school has no way of paying yet. This injustice exists from the smallest scale, at the level of the locality, to the highest, as seen in the case of the hidden debts. At the theoretical-political level, there is great concern when voting is requested, but in practice, corruption spreads more and more, reaching the highest levels.

Can you see corruption at the top of the regime?

We cannot point the finger at one or the other. But the facts that occurred with the hidden debts were irrefutable proof that there is corruption at this highest level of our leadership. Who? It is up to justice to prove that. This corruption is benefited by justice that acts with exemption. Whoever has power easily escapes, or keeps deferring justice. And the simplest ones are hit harder than the others. This differentiation is also a source of dissatisfaction.

The president is a native of the Cabo Delgado province, of Namaua. At a time when the province has been experiencing such a difficult crisis for so many years, would it make a difference for Cabo Delgado to make more appearances in what the president says? And for him to have a more regular presence here, going to Palma or to the districts closest to the occupied by insurgents to comfort the people?

I don’t know what the president’s agenda is. He is a native of Cabo Delgado but the president of the entire country. And he must govern the country without placing more privileges on this or that [province]. When there is a situation like this, in which there is barbaric violence, with a serious violation of the elementary rights of the human person, of the right to life, to housing, to the land, when it happens not to one person or two, but with entire districts becoming depopulated, if I were president, my concern would be different. My presence would be different. This would be high on my agenda. I would be talking about this every day. And even delegating other functions. To open a school, I have ministers, deputy ministers, a prime minister. In order to dedicate myself to a cause that really affects national sovereignty, it is necessary to find effective results very urgently and not to minimize such a problem.

Why do you think the president does that?

It’s difficult. Hence our amazement and that of many people. He must have his reasons. What the Mozambican people expect from a government official is not what we see. This raises suspicions that he may know something, or that there is a plan. But they are suspicious. This attitude gives rise to some reservations.

Mozambique has great natural wealth, but it is proving impossible to distribute it among the population. This Total project could help to bridge the gap between rich and poor in Mozambique. Do you think that the way the government and the presidency have conducted this process has put an investment of this magnitude at risk?

What is putting this investment at risk is violence. And the question is: why has the concern not been focused on resolving this violence, so as not to jeopardize everything else? It was always minimised until reaching this point. There must be other interests that are not public.

How do you see the reluctance towards the participation of international troops in resolving the conflict?

The discourse of preserving sovereignty has no firm foundation in ethics. We cannot speak of sovereignty when there are people dying and we do not defend them or the territory, using the means that can move us forward and preserve life. The question would be: Then, what is being done to defend people’s lives and the territory? It is useless to say: “I do not bring anyone [in], because I want to keep all of my house with integrity”. But your house is on fire, and you will be left with nothing. It is better to ask the neighbours to come and help with water to solve this problem. Human life is above any other type of negotiation. To defend life, we have to do everything, including overcoming things that we normally shouldn’t be doing.

Strategically, should there be military involvement from southern African neighbours?

I cannot enter the strategic field. I enter the field of defending life. It is an ethical and moral field. Between material gains and the defence of life, I defend life. Between talking about national sovereignty in a very fundamentalist way and defending life, I prefer life. We cannot get to radicalism and put sovereignty as something that goes beyond people’s lives. Sovereignty is in favour of people’s lives. The defence of territorial integrity aims at the well-being of the people who are there. If that well-being is violated, how can one talk about that? This is the bishops’ perspective. Strategy is for the military. We have nothing against the involvement of the international community.

Bishop Luiz Lisboa gave a recent interview in which he accused the government of having threatened his life. Did you follow this process? How did you read these statements?

This is from D. Luiz. There are things that can be shared between bishops, and things that are more personal. He was probably talking in that more personal forum …

But an alleged government threat to a bishop is not of the personal forum …

The threat can happen individually. If he said …

But it is an institutional issue …

No, the church has never been threatened by the government.

If the bishop has been threatened, isn’t that a threat to the church as a whole?

Of what we know as bishops of the Episcopal Conference of Mozambique, what was spoken of was never on the agenda. And I’ve been a bishop for two years. We never had the perception that the Mozambican government was threatening the church.

Isn’t the threat to a bishop a threat to the church?

Everything that we bishops say will find an echo. This echo can be one of acceptance or rejection. I cannot assume that anyone in the government who speaks out against that is a very serious threat to my life. It is a person, an entity, a newspaper. It’s public. In the face of D. Luiz’s pronouncements, there were newspapers making personal attacks and commentators linked to the government side speaking out against him.

Do you fear being threatened by the government?

The principle of bishops is one of neutrality. We have had fully closed, nationalised churches. During the war with Renamo, we had missionaries killed and kidnapped, bishops in captivity on the Renamo side who were mistreated. We are exposed to violence because of the church’s integrity and neutrality. If I say something that someone doesn’t like, it can happen. But the church acts on what it thinks is the right way.

Is the Church a government target?

It is difficult to measure. Whether it is the target of the government or of the insurgents in Cabo Delgado, it is difficult to measure. We are constantly evaluating what is happening, and give testimony as a church. We will always do so with truth and as people of faith, who preserve the values of the Gospel.

Are you afraid of an attack by the insurgents, that they will come to Pemba and enter?

Fear is natural. We feel like human beings. But there is no fear here right now. There is a fear when someone shoots, that leads us to say: “This could hit me, better to bow my head!”. This will exist in all of us.

Not only the act of shooting, but also the brutality of cutting the bodies.

Yes, this is paralysing. We have taken action in relation to missionaries, in areas where insecurity is greatest, because they are in the zones at the limit, where they [insurgents] are known to be there, and there is no normal state presence. In these border zones, many missionaries are no longer there.

Is there no one from the church?

The church is there. Christians are there. Where the possibility of praying exists, there will be prayer. They will come together. Now, for Easter, they came from Macomia and elsewhere to seek holy communion. Lay people, animators, catechists. These missionaries, many foreigners, under the guidance of their embassies, have retired, but return to visit the Christians.

When do you see having priests in Macomia, or in Palma again, or in other places where the government guarantees to have the situation under control?

In Macomia, the priests and sisters have come this side. We can only predict a return when security is guaranteed. I don’t think it will be for now.

Do you have an escape plan?

We will meet in the coming days to measure, evaluate and discern what is being said. The feeling of insecurity is now widespread throughout the province of Cabo Delgado, which is our diocese of Pemba. Let’s evaluate.

Will you leave?

No, not as long as there is still a minimum of security. When there is no more security, I will not be leaving alone, but we will also have to mobilize many other people to leave.

At what level? When there is an attack here in Pemba?

This too. If there is an attack and it is not repelled, and we see that life is at great risk, we will have to take more responsible positions.

Are you going to Nampula?

We don’t know, but it is a possible destination.

Will you let believers into the church if there is an attack in Pemba?

The people of Cabo Delgado are already aware of what happens when there are these types of terrorist attacks. In other wars, the church was a safe haven. But I don’t know if in this type of attack the church is a safe place. Neither in Mocímboa da Praia nor in Palma did people flee to the church. People quickly tried to reach a safer area, such as the forest.

Have you had faithful on the run asking you for help directly?

I’ve been in office for a month now. I arrived on February 25th, and, before completing a month, on March 24, the Palma attack took place. When I arrived, one of the concerns was Palma, because there was no way out and it was under siege. We had information that there was hunger. Certain IDP villages lacked food. We mobilised to buy food there, we made contracts with traders in Palma. When I arrived, one of the first jobs was getting our assistance out there. When the attack happened, we still had a truck waiting for the boat to be able to go there.

Then we had to manage various aspects, such as calls from those who arrived in Tanzania and had contact with the diocese, to ask for help – we referred the matter to UNHCR (UN Refugee Agency). People got to Mueda with help from the Tanzanian government.

Did you personally hear stories of displaced people?

I started taking care of displaced people when they started arriving here in Pemba. Some came to ask for transport to go to relatives in Nampula or Maputo. We also had families of our employees who were there. One who helped distribute food in Palma arrived in Pemba at 11:00m a.m. on the day of the attack, and at 4:00 p.m. came to say: “Mr. Bishop, they are attacking. I just spoke to my wife, they’ve already cut off communications and I don’t know where she went. I tried to persuade her to run away, and I don’t know if she managed to escape or not”. He was weeping constantly. This Christian later managed to get his wife to Pemba. He came here with the wife and I heard the account of how she escaped. He was carrying a child, the wife’s nephew, with a bullet in his body. I saw it, because they extracted the bullet.

What was the story that most impressed you?

It was of a young man who was in a confrontation with the insurgents. He was in the military, but then he had an accident, was demobilised and got a job in the state apparatus. He was working in Palma with a certain responsibility. When he returned from work, he was going to open his door, saw people running, asked what was happening and heard that the Al-Shabaab were coming. He ran to the nearby police station, because he knew the commander, and warned him that they were coming. They gave him a gun, because the commander knew he was a former military man, and they engaged in the confrontation. But he said that shortly afterwards they could no longer continue to fire because the insurgents were approaching more and more, with powerful weapons and grenades, destroying things, including the police station where he was. So he had to run to escape the place with the other police officers. He escaped and managed to reach Afungi [next to Campo da Total, half a dozen kilometres from Palma]. There were already a lot of people there. He had a very strong leadership role in trying to publicise what was happening. He made an audio message about how to get through, which reached many people. And he was very scared. Another testimony from other people confirmed that he had a very important role, he was the one who organised people to sit and receive water, there was no leadership in face of that mass of refugees, and he did a very good job. A brother of his was able to pay for a plane ticket from Afungi, and he came here and told me first-hand what had happened, but also that he feared for his life, because of the leakage of information. He did not know what the reaction of the others was. And he left here in silence, until he reached the family home. Today, he is fine.

It also shows that there were not enough military or weapons in Palma.

That was not the problem. What was seen in Palma is that the insurgents showed a very sophisticated strategic mind, that they had studied everything and that they used the principle of an improbable hour to catch the others off guard. They would have thought that the hours of readiness would be different. This slightly disrupts the organization and immediate response.

Do you think you may have infiltrated insurgents in Pemba?

The way in which they operate leads us to think that they are more likely to have infiltrated not only here in Pemba, but also elsewhere.

What can Portugal do if it wants to be useful to help in this conflict?

I appreciate what has already been done. The diocese of Pemba has the help of many brothers in Portugal. We have an agreement with the Braga diocese to send missionaries who have come here and in Braga we have four seminarians of ours. I know that many in Portugal pray for Cabo Delgado. I have received messages of support from people who say they are praying for Cabo Delgado. This spiritual path brings Cabo Delgado and the Portuguese people closer together. In terms of material aid, there are also several groups that organise themselves. Groups of friends, non-governmental organizations, raise funds and deposit in the emergency account of the diocese of Pemba. That help has been coming. I want to thank them, on behalf of the diocese of the people of Cabo Delgado, for all these gestures.

Portuguese Caritas is also involved in this great chain of mobilising support for Cabo Delgado. We are united and we thank them immensely for everything that arrives. Of the Portuguese in general, we have seen a great effort to make known what is happening in the north of Mozambique. Portugal has been a lawyer for Mozambique in this case. I think it is worthwhile continuing to involve the whole world, because it may be that the roots of this problem are not in Cabo Delgado but have several other connections. In a global world, insurgency and terrorism must be faced on the spot, but also at the international level. Portugal can play a big role in this international discussion.

Will the relationship between the Church and the Islamic community in Mozambique be hurt by this conflict?

It will not be. This relationship is centuries old, and the Islamic community, via its Islamic congress bodies, distances itself from the perpetrators of this violence. They have always said that it has nothing to do with the principles of the Islamic religion in which they believe.

Would you be surprised to discover that there are boys with Catholic backgrounds among the insurgents?

I would not, because we have some who are in the insurgency not of their own free will, but to save their life. They can pretend that they are no longer Catholics and have converted to Islam. As little as I know, it is one of the conditions for preserving life when they are captured. Either they make out they are willing to switch to the Islamic religion or they die. Whoever thinks he needs to preserve his life can play the role that he is on the other side.

Are you willing to welcome these young people if they manage to free themselves?

They are children of the house. The church will always welcome, not only these, but everyone else who wants to be part of the path of good …

But they have to show regret for having participated in these acts …

Yes, this is a path of mercy that the church knows how to embrace.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.