Mozambique: Happy belated 65th anniversary dear Gorongosa National Park!

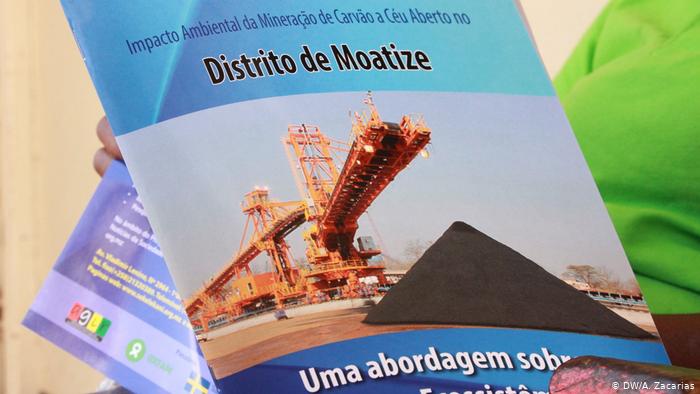

Food with coal and contaminated water: the daily lives of Moatize residents

File photo: DW

NGO research warns of the health risks of mining activities for residents of the Moatize district in Mozambique. Vale says it is implementing changes to mitigate the impact of coal mining on communities. [Full report (in Portuguese) HERE]

A study by the non-governmental organisation Sekelekane, released on Tuesday (06/30) in the city of Tete, scientifically analyses the socio-environmental impacts of coal mining in the regions of Moatize and Benga by mining companies Vale Moçambique and ICVL.

The results of the study point to profound changes in water and air quality.

Regarding air quality, the study says that suspended particles detected include sulphur dioxide, carbon monoxide and dioxide and nitrogen oxides.

The document also assesses the level of noise pollution from dynamiting, and concludes that “the average value recorded goes well beyond tolerable levels”.

Living near the mines

João Tomo lives in the Nhatchere neighbourhood, outside the city of Moatize, one of the residential areas closest to Vale Moçambique’s mining operations, and tells of the drama of living near a mine.

“My house is next to the Vale mine. When they detonate the rocks, all that dust gets inside our flour. I once asked my wife to bring moringa leaves for curry, and they were completely covered in coal dust. We washed and ate them, even though it’s harmful to health,” João Tomo says.

According to Ana Piedade, a researcher at the Zambezi University and co-author of the study entitled “Environmental impact of open pit coal mining in the Moatize district”, exposure to coal dust can cause various respiratory diseases.

“Both those who live close by, and residents here in Tete [city], will suffer from these diseases after a period of time,” Piedade reports. Concerning mining, one is “talking about dust, and the lungs suffer most from exposure which, in time, may cause tuberculosis”, she warns.

Another Bairro Nhatchere resident, Maria Sicreia, says that “people where we live have breathing problems, conjunctivitis and tuberculosis”.

“We have the rural hospital in Moatize, but health personnel cannot explain the origins of the diseases. We have tried to protest this problem, but they only prescribe for what it is that they understand, and we remain sick,” she says.

Ana Piedade says that there is still no mechanism in the health sector to examine the relationship between respiratory diseases reported by communities and the exposure to mining dust.

The researcher calls for “the result of exposure to coal dust to be entered into medical records so that doctors can better diagnose patients”.

Complaints have a scientific background

Tomás Vieira Mário, executive director of Sekelekane, which commissioned the study, says that it is also necessary to look at the sociological impact of mining in Moatize.

“There have, over the years, been complaints of desecration of graves, and harm to the spiritual side of communities. So this document has the merit of giving a scientific basis to communities’ perceptions,” he notes.

Vieira Mário also points out that “there must be a formal and official complaints mechanism which brings together communities, the government and [mining companies], so that complaints are not poorly managed, in a piece-meal fashion”.

DW Africa tried unsuccessfully to speak to Tete’s provincial Land and Environment Directorate about the study’s findings.

Brazilian mining company Vale Moçambique told DW Africa via email that it is developing a series of socio-environmental activities in Moatize as part of its environmental management plan, citing the planting of a ‘green curtain’ on the border between the mining area and local communities to minimise dust emission.

Vale also says that it monitors meteorological conditions, air quality, noise, vibrations, water and effluent quality, waste management and environmental education training.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.