Mozambique: Parliament just closed its first session of the current legislature - Watch

Covering Samora Machel’s death was harrowing – South African journalist Sol Makgabutlane

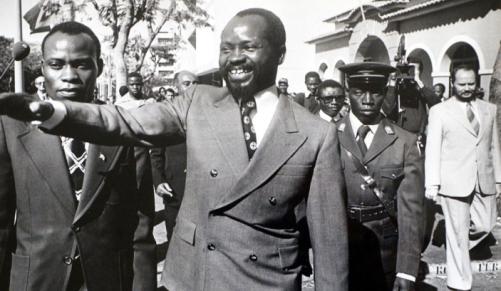

Independent Media / Jim McLagan / Samora Machel goes to meet the people of Maputo soon after independence.

Shoes, severed human limbs, empty soft drink and liquor bottles lay scattered around the wrecked aircraft as though in mute testimony. With the relentless lowveld sun beating down, the odour of dead human flesh was beginning to permeate the air.

Samora Machel goes to meet the people of Maputo soon after independence. Picture: Jim McLagan. Credit: INDEPENDENT MEDIA

I noticed all of this as a thousand thoughts raced through my mind, and overwhelming sorrow gripped my psyche. It was almost impossible to digest the magnitude of the tragedy that lay before us.

The day had begun ordinarily enough. I was on the 7am shift at The Star. I stepped into the newsroom on that Monday morning, October 20, 1986, neatly dressed as always in collar, jacket and tie as I had been taught at the cadet school from which I had graduated a few years earlier. I was ambling to my desk to take off my jacket and scan the morning papers to see what the week held in store.

But as soon as I walked in, I noticed a great deal of excitement at the news desk at the far end of the building. A number of news desk staff – Ron Anderson, Viv Prince, Phil Mtimkulu, Peter Mann – were talking animatedly. One of them – I cannot recall exactly which – called me over.

“There’s been a plane crash on the border with Mozambique,” one of them blurted, “and we suspect it was carrying Samora Machel.”

Since it was October, this was no April fool joke.

I was informed that the newspaper was hiring a chopper to take a team to the scene. In no time I was in the car with journalist Claire Robertson and photographers Etienne Rothbart, Clive Lloyd and Yacoob Ryklief, racing to the Rand Airport in Germiston.

The 450km distance from Rand to the crash site, south of Komatipoort, was a blur of emotions and despair. I did not know what all of this would mean if the news of Machel’s demise proved to be true.

The area was hilly and bushy. Our helicopter made wide sweeps until we spotted some wreckage, landed and were promptly detained by the South African police team already on the scene.

The officer in charge said we were fortunate that we had not been shot down by the Mozambicans as our helicopter had actually crossed the border into Mozambican airspace. This made sense, as the plane was only just on the South African side of the border.

From where we were confined by the police – under a fig tree a couple of hundred metres from the wreckage of the Russian-made Tupolev TU134 – I could make out the aftermath of the crash. A crew from the World Television Network also landed a few hours after us by chopper and were made to join us under the tree.

At 1.25pm, a senior South African government delegation led by foreign minister Pik Botha landed. Among the delegation with Botha was the commissioner of police, General Johan Coetzee, and Lieutenant-General Denis Earp of the SA Air Force.

Shortly thereafter, a Frelimo delegation from Maputo, led by Mozambican minister of security Sergio Vieira, and deputy minister of health, Dr Fernando Vaz, also touched down.

There were about 20 other Mozambican government officials.

Ignoring Botha’s proffered hand, Vieira demanded to be taken at once to the wreckage. Botha and his team then led the Mozambicans to the mangled Tupolev. After the necessary formalities and inspections, Machel’s body was identified – and the mutilated remains were placed in a coffin and loaded into an air force helicopter that had come from Mozambique.

Among the bodies repatriated to their country was that of Machel’s special assistant Fernando Honwana. Later I learnt that other senior government officials who died included transport minister Alcantara Santos and Carlos Lobo, the deputy foreign minister.

The then South African police media liaison officer, Brigadier Leon Mellet, a colourful character who was also a photo comic actor, allowed us to approach the wreckage to observe and photograph, with strong injunctions not to disturb the accident scene which had now been secured by the army and police.

All of this was like a scene from a nightmare. Samora Machel, a cult-like hero to black people, lay dead, his skull crushed. The aircraft had been carrying 38 passengers and crew, and more than two dozen Mozambicans and Soviet nationals lay dead on that hill.

The aircraft had taken off the previous night en route from Zambia to Mozambique.

The cause of the crash would later prove to be a subject of speculation, angry accusations and heated denials between the Russians, Mozambicans and South Africans.

Although at the time I had covered the unrest raging on the Witwatersrand, the Machel plane crash was my first big, international assignment. And the fact that a much-loved and respected liberation icon had died, left me in emotional turmoil.

Residents of Mbuzini, the Eastern Transvaal village where the tragedy took place, were beside themselves with sadness. Almost all had heard the gigantic noise when the plane went down. Some said they thought it was loud thunder. Others reckoned it was dynamite blasting.

Thalitha Mashigo, whose homestead overlooked the site, said it was a dark and overcast Sunday night when the silence was shattered with what sounded like a enormous explosion.

She said: “A short while later, we heard a (Mozambican) man screaming and crying outside, saying: My leader has been killed! Machel has been killed!’ He was covered in blood and severely grazed.”

He was later identified as one of the dead president’s bodyguards from the doomed twin-engined jetliner.

Mbuzini headman William Nyambi told me: “I was asleep when a woman and boy came to wake me up and said there was a person who had been injured in an aircraft accident. We rushed to the woman’s house and found the injured man. We took him to the clinic where he received medical attention.”

It was the medical staff at Mbuzini clinic who notified police of the tragedy.

Carried away from the crash site, Samora Moises Machel’s remains looked ordinary, even small in stature. Yet this simple man, a former hospital orderly, had cast a giant shadow over the region as he faced the seemingly invincible apartheid edifice.

He had assumed almost superhuman stature.

As I listened to the car radio in Mbuzini, I could pick up a station being broadcast from Maputo, 100km across the border. Although I could not understand the language, it was crystal clear from the tone of the voices which were interspersed with martial music: Mozambique had lost a fearless hero and gallant champion. An indefatigable warrior.

Graca and Samora Machel on their wedding day in 1975.

I pondered on what the future held for Mozambique in Machel’s absence. Mozambique then faced the twin threat of Renamo internally and the apartheid government outside.

Indeed, I wondered what was in store for South Africa’s oppressed majority, for whose freedom Machel had been playing such a prominent role.

As night fell, with the images of the dismembered, doomed passengers lying in the Mbuzini sun tormenting my subconscious, and the music coming out of car radio speakers, I was enveloped by an overpowering feeling and suddenly, inexplicably, the Negro spiritual floated into my mind:

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot

Coming for to Carry me Home.

By: Sol Makgabutlane

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.