Mozambique: Four killed and four children missing after attack on Napala village - Lusa

Cabo Delgado free-for-all – Special Report | By Joseph Hanlon

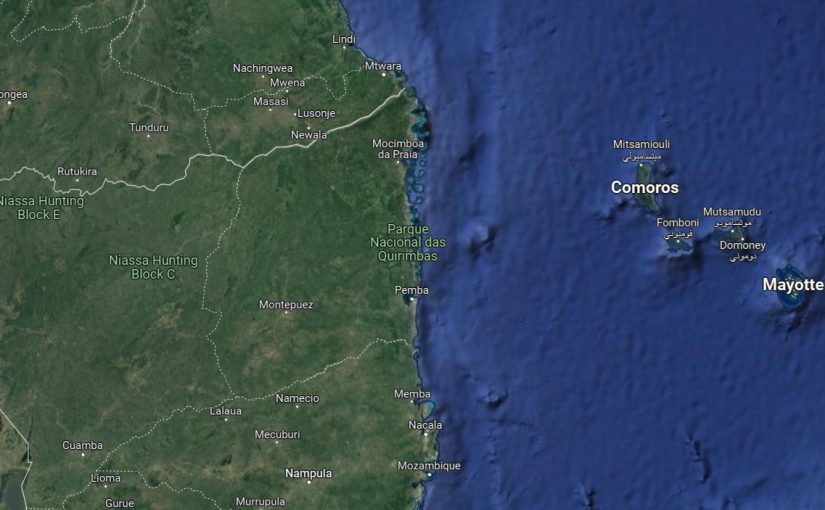

Image: Google Maps

Why is Cabo Delgado a free-for-all?

Wars involve big money and huge suffering, so they attract business and the aid industry. Cabo Delgado is no different, and it is becoming a playground for international agencies, donors, and INGOs, as well as Mozambican civil society, business and the Frelimo elite.

President Nyusi has recently been touring the world trying to raise more than $600 mn per year to pay for the war. International agencies are fundraising for hundreds of millions of dollars for humanitarian assistance. The World Bank approved $450 mn in projects for the north in December and $350 mn earlier in 2021.

The big money and international attention have been aimed at a return to what was there before – rebuilding roads and schools and administrative offices, and helping the displaced until, sometime in the future, they can return home. There is, so far, no addressing of the roots of the war and the huge inequalities of Cabo Delgado.

This is a personal exploration to ask: why? I am a long-time writer on both Mozambique and civil wars (Civil War, Civil Peace ). I have no answers, but I try to point to a series of factors which I believe shape the present stasis. Divisions within Frelimo and its governance style both play a role. The limitations of the international aid industry are important. And many people profit from the war. I start by looking at the humanitarian aid industry, at a historic success in coordinating it, and at the failure so far to impose any more than informal restrictions in Cabo Delgado. And I end by asking: If so many people are gaining from the on-going war, is there little motivation to stop it?

We have been here before

The 1980s US-driven proxy war caused a million deaths and huge destruction, but after Mozambique’s “turn to the West” in joining the World Bank and IMF and allowing in INGOs, there was a huge flood of aid. As is occurring now, this led to confusion. In 1987 the government created CENE (National Executive Commission for the Emergency, Comissão Executiva Nacional de Emergência) headed by then deputy trade minister, Prakash Ratilal. He quickly brought donors into line.

Within a month, Ratilal set up two weekly meetings. On Saturday morning there was a technical meeting of port and transport officials to break aid bottlenecks. The Monday morning meeting included NGOs, donor countries, and UN agencies, including UN special emergency coordinator Arturo Hein. All were equal in the Monday meetings, with Ratilal in charge. He forced the meetings to be in Portuguese and not English, and soon made clear it was not possible to bypass the government. He also forced donors to air their complaints at the Monday meeting, instead of at diplomatic cocktail parties. But he was also skilled in promoting donor collaboration, and he drew donors into helping set government policy.

Ratilal had one other important success and one failure. He succeeded in having individual donors concentrate in a single district rather than spread their aid thinly across the country. But he failed to convince donors to shift from humanitarian to development aid, to help people grow their own food rather than depend on donations. As now, pictures and reports of food and humanitarian aid always look better – to members of parliament approving budgets and individuals giving money to INGOs. (Detailed in chapter 8 of my 1991 book Who Calls the Shots, free on http://bit.ly/Hanlon-books)

No coordination, no one in charge

Thirty five years later, the government does not seem to want that sort of coordination, and nothing like the 1987 CENE has been introduced for this war. There appears to be no coordination and no one in charge of what happens in Cabo Delgado.

The only formal government coordination is ADIN (Integrated Development Agency for the North, Agencia de Desenvolvimento Integrado do Norte) which has substantial money from the World Bank. Although it stresses a focus on youth employment and small business, it has no clear strategy. Its website https://adin.gov.mz/ page on policies and strategies is simply principles for developing a strategy. ADIN is under the umbrella of super-minister Celso Correia.

A $490 mn Reconstruction Plan for Cabo Delgado (PRCD, Plano de Reconstrução de Cabo Delgado) was approved by the Council of Ministers on 21 September 2021. https://bit.ly/CDg-Reconstruct It is mainly for infrastructure rebuilding – $146 mn for bridges, roads and transport; $70 mn for water and energy; and $60 mn for health and education. Humanitarian assistance is planned for $150 mn and is labelled social protection, but much of that is for reconstructing buildings. Rebuilding economic areas such as fishing and agriculture is budgeted for $15 mn. The money is divided as $190 mn for “quick win” projects in the first year and $300 mn in the next three years.

On the donor side, a decade ago donor coordination and links with government had been through the Budget Support Group. With the secret debt crisis in 2016, budget support was ended, and the group stopped. There was no formal donor coordination nor collective links with government for three years. The regular dialogue with government “has fallen away” admitted EU ambassador António Sanchez-Benedito Gaspar in 2019.

So in late 2019 two groups were created. The Development and Cooperation Partners (DCP) group is led by the EU and the USA. An alternative International Community Covid-19 Taskforce (ICCT) was created with Foreign Ministry participation to deal with Covid-19. It is headed by Ireland and the UK and has been relabelled the Crisis Taskforce (thus still ICCT) and is moving into being the donor coordination forum for Cabo Delgado.

The real issue is: What is to be done? The World Bank, African Development Bank, UN and EU worked with a government team led by Celso Correia to develop the Resilience and Development Strategy for the North (ERDIN, Estratégia de Resiliência e Desenvolvimento para o Norte). Donors thought they had agreement of government on the draft in October 2021, but Frelimo has refused to submit it to the Council of Ministers. It is apparently seen as too donor driven, and raised the issues of jobs and lack of local involvement which remain disputed within Frelimo.

And there are a host of individual donor-government projects. For example, on 26 March the Ministry of Industry and the African Development Bank launched the Pemba-Lichinga Integrated Development Corridor Special Agro-Processing Zone.

Divide and Rule

President Filipe Nyusi, since he took office in 2015, has developed a system of competing power centres, with only him at the top. It was the Ministry of Economy and Finance versus the Bank of Mozambique. The Cabo Delgado war was divided between the army and the police.

In addition, Nyusi brings in powerful outsiders. Most obvious was bringing in the Rwandan army and police to fight the war. Celso Correia, Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development, is very powerful. And powerful and politically well-connected businessman Constantino Alberto Bacela was made Minister in the Presidency (for “casa civil”) in November.

Thus at all levels, it is set up to be a “Game of Thrones”. People rise and fall in the eyes of Nyusi and Frelimo structures. The March reshuffle of top ministers and the bitter infighting leading up to the Frelimo party Congress in September create further uncertainty.

And this has a real impact on Cabo Delgado. With Celso Correia in charge of both ADIN and ERDIN those seemed safe as setting the agenda. But the diminishing role of both may be linked to reports that Correia had fallen from favour last year. Recent reports suggest he may be regaining favour. But it all leads to a feeling that no one is in charge and there is no policy.

Modest decentralisation had occurred in the 2000-2015 period, but this has been reversed, again with competing power centres controlled from Maputo. At local level there are elected governors and mayors, as well as appointed district administrators. Nyusi created a dual system in which these people are matched by Presidentially appointed secretaries of state, with an unclear division of powers.

How this is used is clear from the Reconstruction Plan for Cabo Delgado (PRCD) which is entirely centrally controlled by the President and Council of Ministers. At the provincial level, implementation is led by the Provincial Secretary of State, directly appointed by the President, with the elected Provincial Governor explicitly relegated to an “assistance” role. The provincial implementation forum consists entirely of people appointed from Maputo. The UN, civil society, and development partners are, literally, “guests” who are expected to work through ADIN and ministries.

PRCD is entirely central government controlled, with no role for civil society, although Maputo-based civil society has been trying to organise Cabo Delgado civil society to press for involvement. Cabo Ligado Monthly (October 2021 http://bit.ly/Ligado-Oct21) said “such a system could leave Cabo Delgado citizens with even less local control over their political future than they had before the conflict.” One senior aid official told me “we are making plans for people without talking to them.”

Grievance?

The sharp division over the roots of the war is one reason for the stalemate over how to move forward.

President Filipe Nyusi stated publicly in Brussels in February that Mozambique has no responsibility for the war in Cabo Delgado, and that it is entirely caused by foreign militants. Whether or not Nyusi believes this, it is Mozambique’s official policy. But most people who have looked closely at the war accept, at the minimum, that there is a grievance – that young people are angry about lack of training and jobs, of marginalisation, and of not benefitting from the resources of the province. And it is widely accepted that, at the very least, militant organisers have been able to take advantage of this grievance to recruit several thousand insurgents. Even within Frelimo there is demand to look at the grievances. “I know there is a great resistance to recognising that there are internal causes that facilitate the penetration of terrorists within communities, but it is a fact. We cannot think that it is just infiltration from outside,” said Graça Machel on 11 April at an event of her Foundation for Community Development (FDC). (O Pais, LUSA 11 Apr)

Unexpectedly, Radio Moçambique, on 11 April reported that “unemployment and lack of opportunities, namely in emerging gas-related investments, have been pointed out by various observers as some of the causes of recruitment of young people from Cabo Delgado to the rebel groups.” Coming from the state broadcaster, the suggests a growing rebellion within Frelimo against the Nyusi line.

This has a very practical effect. The Reconstruction Plan for Cabo Delgado (PRCD) contains no job creation or skills training. Machel attacked ADIN directly, saying its response is purely “economic and very little geared towards wound healing and human development.”

The draft ERDIN (Resilience and Development Strategy) says that “at the root of this insurgency are perceptions of inequality, exclusion and marginalisation [and] perceptions of injustice in the distribution of benefits and opportunities arising from extractive activities.” And it calls for more “inclusive and equitable access to public services” and to “strengthen inclusive governance, with a focus on citizen participation [and] fighting corruption”. Government representatives on the working group clearly thought this would be acceptable, but in practice a report that says this cannot be presented to the Council of Ministers.

Admitting the existence of the grievance is seen by some people in Frelimo to be admitting at least partial responsibility for the war, which they are not willing to do. So it leaves ADIN, civil society, and donors trying to deal with the grievance without saying so. And this problem seems unlikely to be resolved until after the Frelimo party Congress in September.

Jobs and training

As part of “corporate social responsibility” TotalEnergies is to train 2500 young people. The first 120 will be from camps of displaced people. The training will be for electricians, carpenters, bricklayers, plumbers, painters, and solderers.

But TotalEnergies is not promising to hire any of these people, probably because the 3 to 6 months training is too basic for jobs offered by TotalEnergies for the LNG project. Apprenticeships of the sort normally demanded are a minimum of 18-24 months after the basic training offered in this scheme.

So young people will see it as just another token project. To stop the war, thousands of young people have to be given a job and a future. Apprenticeships could be linked to rebuilding cities now back in government control such as Mocímboa da Praia, Macomia, or Quissanga. On the job apprenticeships would be two years, and those who passed would have to offered a job at least for two or three years. The whole point of ADIN or serious donor involvement would be to provide the five year guarantee – of apprenticeship level training and then of a job. It might need to start with basic literacy and numeracy, because many young people in Cabo Delgado have only four years of primary school.

Unfortunately donors all say this is impossible. None can do five year projects; most say they are not implementing agencies; none would be prepared to guarantee jobs at the end of the training. Also few aid coordinators, ambassadors or development bank officials are in Mozambique for five years – and their bosses in Brussels or Washington or other capitals will also move on. So any project, from design to finish, must show results in less than three years.

Many agree on the need for serious training and job creation, but all say someone else must do it.

Business and politics as well as aid

So far our discussion has appeared to resolve around aid, but the stalemate over Cabo Delgado is in part due to two other players. As well as the aid industry, business and Frelimo are also trying to profit from the war.

Many businesses profit from the war, supplying everything from vehicles to food. The also profit from servicing the gas industry. At one end are the war profiteers. They range from military and security officials who siphon off food rations and money from supply contracts, as well as who organised the looting of Palma. At a lower level they involve police and soldiers on check-points or shaking down pedestrians and who want money or steal mobile telephones.

For Frelimo, the profit comes from patronage and commissions. Its control of land, contracts and licences leads to a pyramid of patron-client relationships. Frelimo oligarchs and lower level people with party power give war and aid contracts to those who pay commissions and offer other services to the party.

Even honest and professional business people have to be part of the Frelimo patron-client regime to survive in Mozambique. Humanitarian and reconstruction aid is mostly managed by Frelimo-linked organisations and businesses with generous commissions along the way. Cabo Ligado Monthly (October 2021) noted this is built into the budget of the Reconstruction Plan for Cabo Delgado (PRCD), where there are huge differences in prices for basic such a tents and photos of President Nyusi – clearly a way to leave ample space for money to be allocated by Frelimo.

Nyusi’s divide and rule, and centralisation, are ways of keeping control in Maputo – to ensure the “right” people win the contracts and the “right” people are paid commissions.

It is useful here to introduce the 18th century US revolutionary and inventor, Benjamin Franklin. He called on people to “Do well by doing good” – which means to profit by doing good. This phase has become a proverb precisely because the words “well” and “good” have very wide meanings in English. Thus an insurgent fighting a greedy government, a soldier fighting “terrorists”, and an aid worker helping the displaced can all believe they are “doing good”. And “doing well” can be monetary profit, but it can also be helping to build institutions and NGOs, and also gaining social status and prestige in the community. The axiom captures the US stress on philanthropy by the super rich, and the 2010 call by Bill Gates and Warren Buffett for fabulously wealthy people to give away half their wealth. The underlying point is that profit need not be financial, but can be social or institutional.

Most of the people involved in the war economy believe they are “doing good” – soldiers protecting the country, businesspeople taking risks on dangerous roads to get food to soldiers or displaced people. “Doing well” usually means making a good profit. But it also has a social content. Many business and Frelimo people gain significant local status and respect by giving money to charity and religious bodies, creating jobs for the community, and becoming the person of standing that local people in need can approach for help. Companies maintain their status though “corporate social responsibility” or local charity. In a similar way, Frelimo leaders gain local standing because they distribute contracts and commissions. Thus “doing good” also means helping your own community, and “doing well” also means gaining local respect and prestige.

The aid industry is at the centre of ‘doing well by doing good’ in a continuing war

Much of the profit to business and Frelimo comes, indirectly, from the World Bank, EU, bilateral donors, UN and international agencies. The huge aid industry has its own definitions. Of course promoting development and succouring the hundreds of thousands of people hit by war and cyclone is “doing good”. “Doing well” in the aid world is partly personal – earning a good salary or getting promoted or becoming influential. But in aid, “doing well” is often institutional – donors pleasing their capitals, UN agencies building their role in the permanent UN infighting, World Bank and EU handing out more money, INGOs gaining contracts, and local civil society growing their organisations and salaries

Most donors are proud that they are “doing good”, and that they are doing the best they can under the constraints. Of course they would like to create jobs, but they know they must look for projects that will show results in less than three years – many of which are inevitably workshops and short training sessions, often in Pemba. And they know they are expected to give contracts to consultants and contractors in the home country.

But donor and lender staff are trying to “do good” in the context of another set of pressures specific to Mozambique. On the one hand, the World Bank and EU are under pressure to shovel money out the door. On the other hand, there are constant appeals for humanitarian assistance for victims of the war, cyclones and Covid-19; bilateral donors, INGOs and local civil society are anxious to use that money to build up their presence.

The government survived the very loud donor-cut off of significant aid in 2016 due to the $2 billion secret debt. Government did not collapse in the face of the donor strike. Donors and now the IMF have quietly crept back into the fold, without major concessions by government. Foreign governments want a presence because of the gas and the potential to win huge contracts. So they cannot afford to challenge Frelimo misconduct.

They did not challenge a percentage of Covid-19 donations being siphoned off, and will allow Frelimo to take its cut of humanitarian and reconstruction aid. When the UN, World Bank and bilateral donors want to give money to Mozambique, they are unlikely to look too closely at spending details and policies.

Everyone says they want the war to stop. But do they? Are too many people doing well by doing good in a war that does not stop.

By Joseph Hanlon

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.