Mozambique: Police say teams mobilised to rescue Maputo kidnapping victim – Watch

Cabo Delgado : Battle for Mueda continues; comment on “terrorism” – By Joseph Hanlon

Map: News, Reports & Clippings

The battle for Mueda is on

A key battle in the Cabo Delgado civil war is under way. Mueda town is the Makondi capital and has become the centre of government military forces (FDS) fighting insurgents. It also controls the only open road to Palma and the gas fields.

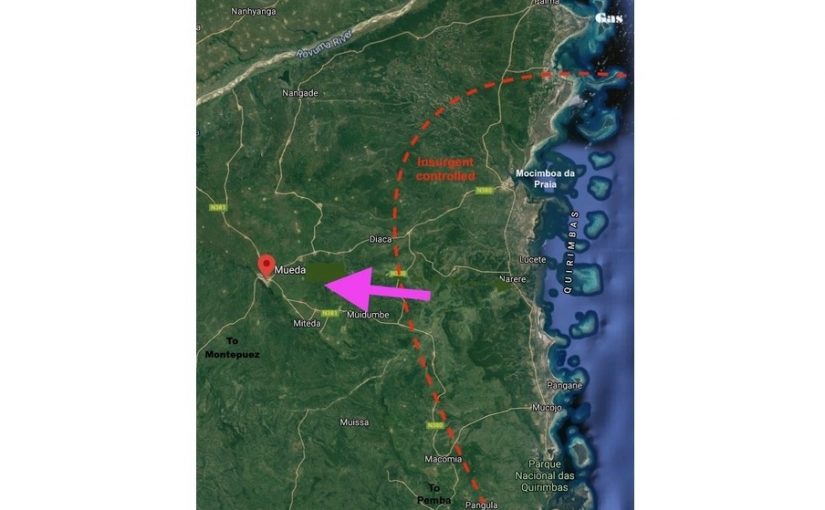

Geography matters. Effectively there is a plateau which reaches 250 metres high and slopes east 100 km to the sea. At the west and north there is a steep escarpment that falls to the Rovuma River. Two centuries ago some Makondi moved to the top of the plateau to escape the slave traders. They established Mueda, which in 1965 became the centre of the independence struggle. The plateau is divided into three districts, Mueda in the west, Muidumbe lower down, and then Mocimboa da Praia at the coast. Mueda and the western half of Muidumbe are predominantly Makondi and Catholic. Eastern Muidumbe and Mocimboa da Praia are mixed but the majority are Mwani and Islamic. The original insurgent force was largely made of young Mwani men.

Insurgents now occupy all of Mocimboa da Praia town and district, which means they control the N380, the only paved road north from Pemba to the gas fields as well as coastal shipping inside a chain of islands. Control of this zone has stopped the repair of electricity lines meaning no power to four districts for several months. Roads going east from Mueda to Mocimboa and southeast to Macomia are also cut. The only open road is a long dirt road from Montepuez to Mueda to Nangade to Palma, which remains open but will become impassable in the upcoming rainy season.

This year insurgents have attacked Muidumbe repeatedly, occupying villages and towns and then being pushed out. After the independence war, many liberation war veterans settled in Muidumbe. Although now older, they have organised militias which have been armed, and they have been effective in defending their home area.

Meanwhile Mueda town has been under threat since the beginning of the month. More than a week ago banks and other businesses as well as health facilities closed and most resident fled. Some are trying to walk the 200 km south to Montepuez. Liberation war veteran and Frelimo Political Commission member Alberto Chipande is said to have moved his family out of Mueda.

Mueda has become a heavily armed garrison town, empty of civilians, and has not been attacked. But there has been heavy fighting in Muidumbe. Many civilians fled into the dense forests where they were sought out by the insurgents. The riot police and militias have recaptured some of Muidumbe, including the district town, Namacande, but the rest of the district remains occupied.

The district administrator of Muidumbe had ordered all civil servants to return by 1 November, and shortly after that the insurgents began their new attack. One of those who had just returned was a teacher in Matambalale, Damiao Tangassi, who was executed in front of his wife and family. A moving homage to Tangassi was published in Carta de Mocambique (17 Nov) and is posted, in English and Portuguese, here: https://bit.ly/Tangassi

MediaFax yesterday (23 Nov) reports that insurgents killed many people, decapitating some, and kidnapped people. They destroyed public and private infrastructure such as the brand new Muidumbe District Government building, as well as the facilities of the local Catholic church and the community radio station it managed. And they burned or demolished many houses.

We no longer publish detailed reports on the Cabo Delgado civil war and advise readers to subscribe to the weekly CaboLigado – free, published on Tuesday, and in English. It gives the best reporting on the war. Subscribe on https://bit.ly/CaboSub and go to the bottom of the form and tick Cabo Ligado.

The number of people dislocated by the civil war in Cabo Delgado and the small Renamo Junta in Sofala now exceeds 500,000, Prime Minister Carlos Agostinho do Rosario told parliament Wednesday (18 Nov)

Comment on ‘terrorism’

“Terrorism” is what the word says: creating terror and fear in your opponent and demonstrating your unchecked power. Aerial bombing of London and Berlin during the second world war, and in Aden now, in intended to terrorise the civilian population. But it is a common tactic of war and does not need an air force. It is particularly important for weaker guerrilla forces to establish their power and image.

In the 1981-92 war, Renamo used terrorism extensively and strategically. For example, an aim was to stop travel, so buses were attacked and passengers burned alive. But Renamo always allowed some passengers off the bus first, so there were people who would tell the story and spread the word. And the horror built Renamo’s image as a serious opposition force. It also proved to be a safe strategy from Renamo. Peace involved talking to terrorists, as it always does. And the peace accord included no prosecutions and Renamo becoming the main political opposition. People who organised and took part in terror are now in parliament and honoured citizens, and no one mentions that they were once terrorists who did terrible things.

Cabo Delgado’s insurgents began small, and used terror selectively – killing identified members of the local elites and those who were known to oppose them. And it worked, winning over young people as recruits and supporters.

The war started in coastal areas where they had support, and executions were mostly selective. When they moved inland to Muidumbe, they faced a more serious Makondi Catholic opposition which successfully resisted. Now it appears tactics have changed, killing larger numbers of people to terrorise civilians to not resist. Like Renamo terror four decades ago, it is structured. Many of the victims are part of the state apparatus, like teacher Damiao Tangassi, and his family were forced to watch and then let go to tell the story.

In early November an estimated 50 people were killed on the local football pitch in Muatide village. The massacre was first reported on 5 November by the Nacala-based Pinnacle News, which has the best sources on the ground, and later confirmed by other local media. It was picked up by the BBC and then other global media, and then condemned by UN Secretary-General António Guterres and French President Emmanuel Macron. It was, however, curiously denied by Cabo Delgado governor Valige Tauabo.

Macron was criticised for calling the massacre “Islamic terrorism” in a tweet (11 Nov). As Islamic State has been made the global enemy, it is convenient for Macron to use that label, but we should be careful. First of all, nearly every person in rural areas has a sharp machete because it is one of the few farm tools they have, and is used for everything from cutting trees to harvesting to cutting open coconuts. The initial insurgent groups had only one or two guns and a few bullets, but all the young men had their machetes, which was used to attack and kill. Of necessity, that became the insurgent symbol.

Second, we have not given religious labels to earlier terrorism. Renamo was taught its terror tactics by the apartheid South African army, but this was never labelled “Afrikaner Christian terrorism”. And the massacres in Mueda in 1960 and Wiriyamu in 1972 were never described as “Portuguese Catholic massacres”.

By Joseph Hanllon

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.