South Korea to ban mobile phones in school classrooms

Aung San Suu Kyi: Myanmar democracy icon who fell from grace

Image: BBC

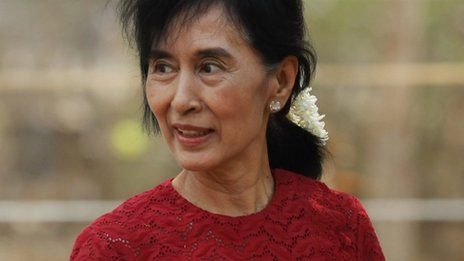

She was once seen as a beacon for human rights – a principled activist who gave up her freedom to challenge the ruthless army generals who ruled Myanmar for decades.

In 1991, Aung San Suu Kyi was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, while still under house arrest, and hailed as “an outstanding example of the power of the powerless”.

But her response to the Rohingya crisis since becoming Myanmar’s de facto leader has precipitated a fall from grace that few predicted.

Path to power

Ms Suu Kyi spent nearly 15 years in detention between 1989 and 2010. Her personal struggle to bring democracy to then military-ruled Myanmar (also known as Burma) – made her an international symbol of peaceful resistance in the face of oppression.

In November 2015 she led the National League for Democracy (NLD) to a landslide victory in Myanmar’s first openly contested election for 25 years.

The Myanmar constitution forbids her from becoming president because she has children who are foreign nationals. But Ms Suu Kyi, now 75, is widely seen as de facto leader.

Her official title is state counsellor. The President, Win Myint, is a close aide.

Political pedigree

Ms Suu Kyi is the daughter of Myanmar’s independence hero, General Aung San.

He was assassinated when she was only two years old, just before Myanmar gained independence from British colonial rule in 1948.

In 1960 she went to India with her mother Daw Khin Kyi, who had been appointed Myanmar’s ambassador in Delhi.

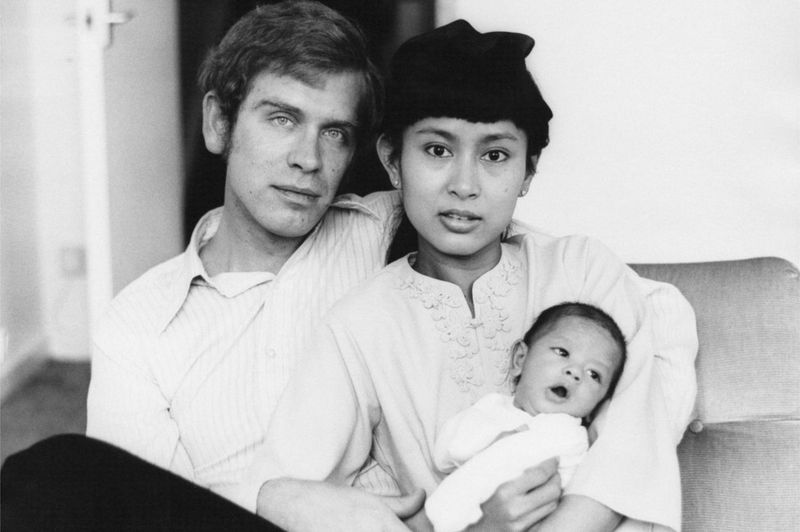

Four years later she went to Oxford University in the UK, where she studied philosophy, politics and economics. There she met her future husband, academic Michael Aris.

After stints of living and working in Japan and Bhutan, she settled in the UK to raise their two children, Alexander and Kim, but Myanmar was never far from her thoughts.

When she arrived back in Rangoon (now Yangon) in 1988 – to look after her critically ill mother – Myanmar was in the midst of major political upheaval.

Thousands of students, office workers and monks took to the streets demanding democratic reform.

“I could not as my father’s daughter remain indifferent to all that was going on,” she said in a speech in Rangoon on 26 August 1988. She went on to lead the revolt against the then-dictator, General Ne Win.

House arrest

Inspired by the non-violent campaigns of US civil rights leader Martin Luther King and India’s Mahatma Gandhi, she organised rallies and travelled around the country, calling for peaceful democratic reform and free elections.

But the demonstrations were brutally suppressed by the army, which seized power in a coup on 18 September 1988. Ms Suu Kyi was placed under house arrest the following year.

The military government called national elections in May 1990, which Ms Suu Kyi’s NLD convincingly won – but the junta refused to hand over control.

Ms Suu Kyi remained under house arrest in Rangoon for six years, until she was released in July 1995.

She was again put under house arrest in September 2000, when she tried to travel to the city of Mandalay in defiance of travel restrictions.

She was released unconditionally in May 2002, but just over a year later she was imprisoned after a clash between her supporters and a government-backed mob.

She was later allowed to return home – but again under effective house arrest.

At times she was able to meet other NLD officials and selected diplomats, but during the early years she was often in solitary confinement. She was not allowed to see her two sons or her husband, who died of cancer in March 1999.

The military authorities had offered to allow her to travel to the UK to see him when he was gravely ill, but she felt compelled to refuse for fear she would not be allowed back into the country.

Re-entering politics

Ms Suu Kyi was side-lined from Myanmar’s first elections in two decades on 7 November 2010 but released from house arrest six days later. Her son Kim was allowed to visit her for the first time in a decade.

As the new government embarked on a process of reform, Ms Suu Kyi and her party re-joined the political process.

They won 43 of the 45 seats contested in April 2012 by-elections, in an emphatic statement of support. Ms Suu Kyi was sworn in as an MP and leader of the opposition.

The following May, she left Myanmar for the first time in 24 years, in a sign of apparent confidence that its new leaders would allow her to return.

The Rohingya crisis

Since becoming Myanmar’s state counsellor, her leadership has been defined by the treatment of the country’s mostly Muslim Rohingya minority.

In 2017 hundreds of thousands of Rohingya fled to neighbouring Bangladesh due to an army crackdown sparked by deadly attacks on police stations in Rakhine state.

Myanmar now faces a lawsuit accusing it of genocide at the International Court of Justice, while the International Criminal Court is investigating the country for crimes against humanity.

Ms Suu Kyi’s former international supporters accused her of doing nothing to stop rape, murder and possible genocide by refusing to condemn the still powerful military or acknowledge accounts of atrocities.

A few initially argued that she was a pragmatic politician, trying to govern a multi-ethnic country with a complex history.

But her personal defence of the army’s actions at the ICJ hearing last year in the Hague was seen as a new turning point that obliterated what little remained of her international reputation.

At home, however, “the Lady”, as Ms Suu Kyi is known, remains wildly popular among the Buddhist majority who hold little sympathy for the Rohingya.

Stalled reforms

Since taking power Ms Suu Kyi and her NLD government have also faced criticism for prosecuting journalists and activists using colonial-era laws.

Progress has been made in some areas, but the military continues to hold a quarter of parliamentary seats and control of key ministries including defence, home affairs and border affairs.

In August 2018, Ms Suu Kyi described the generals in her cabinet as “rather sweet”.

Myanmar’s democratic transition, analysts say, appears to have stalled.

The country is now facing one of South East Asia’s worst Covid-19 outbreaks, putting new strains on an already impoverished healthcare system as lockdown measures devastate livelihoods.

Yet Ms Suu Kyi remains popular. A 2020 survey by the People’s Alliance for Credible Elections, a watchdog, found that 79% of people had trust in her – up from 70% the previous year.

Derek Mitchell, former US Ambassador to Myanmar told the BBC: “The story of Aung San Suu Kyi is as much about us as it is about her. She may not have changed. She may have been consistent and we just didn’t know the full complexity of who she is.

“We have to be mindful that we shouldn’t endow people with some iconic image beyond which is human.”

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.