Italian-Mozambican Jazz Festival kicks off in Maputo

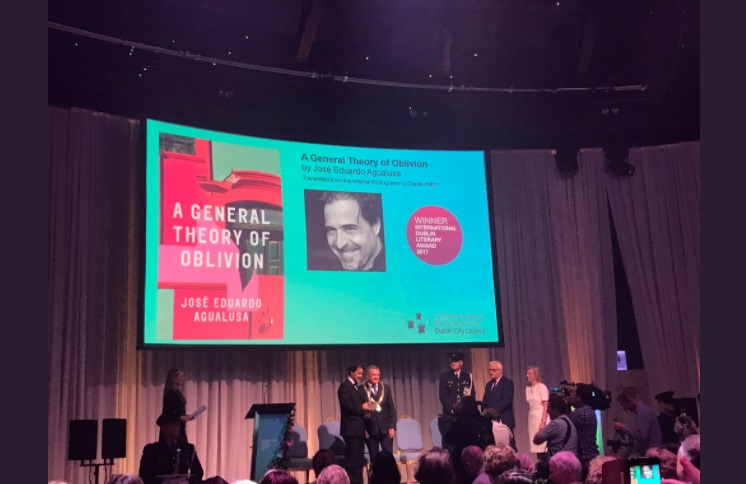

Agualusa wins Dublin book prize, will use money to build a library in Mozambique Island

Dublin Literary Prize Twitter

Angolan writer José Eduardo Agualusa’s A General Theory of Oblivion has scooped the €100,000 (£88,000) International Dublin literary award – formerly known as the Impac prize. The Guardian reports on how he has long desired to build a library in his adopted home on the Island of Mozambique.

“What we really need is a public library, because people don’t have access to books, so if I can do something to help that, it will be great,” Agualusa says, cited by The Guardian. “We have already found a place and I can put my own personal library in there and open it to the people of the island. It’s been a dream for a long time.”

Still according to The Guardian, hanneling money from a prize chosen by librarians around the world into a new library is not lost on the writer. “It is funny … I really appreciate the fact that the prize is chosen by librarians.”

Not that he thought he would be the first choice of those voting in the Dublin-based literary award. “I was really surprised,” he says, on getting the phone call that informed him of his win. “A close friend, Mozambican author Mia Couto, was also on the shortlist, and I really believed he was going to win.”

The book, the writer and the translator

A General Theory of Oblivion by José Eduardo Agualusa has been named as the winner of the prize at a ceremony today. Agualusa will receive €75k of the €100k prize, while the book’s translator, Daniel Hahn – who has worked with the writer on five books – will get €25k.

It was stiff competition for 57-year-old Agualusa: the other nine nominees included Ireland’s own Anne Enright, as well as A Little Life author Hanya Yanigahara.

The book is set in Agualusa’s home of Angola, at a huge time of change for the African country, the eve of its independence from Portugal. As fighting begins between the government and mercenaries, a woman named Ludo retreats to her apartment, even going so far as bricking her door shut to prevent the outside world from reaching her.

The book follows Ludo as she tries to grow her own food, cope with her self-imposed exile, and deal with the changes in her city. It shows how a tragedy led to her withdrawing from life, and becoming suspicious of those around her. A small cast of other colourful characters help paint a portrait of a major time in Angolan history.

With vivid imagery, emotional snatches of poetry that give an insight into Ludo’s state of mind, and its messages about outsiders and racism, the book also found itself nominated for the Man Booker Prize.

Sitting down for an interview with TheJournal.ie yesterday, a delighted Agualusa said that he was particularly happy with his win as “it’s a prize in Dublin, the town with a very old literary tradition”.

In addition, he remarked on the fact the International Dublin Literary Award – whose nominees included his friend Mia Couto – comes from public libraries.

“I think they are very, very important to the development of a country,” said Agualusa of libraries, adding that it’s also an important prize for him “because it’s a prize for the translation, and I really think the translator is essential in the process of success or not success of a book”.

‘I am a liar, I am a writer’

The book is posited to be about a real-life woman, but there’s very little information about such a person online.

Is she real? “No,” smiled Agualusa when asked. “I am a liar, I am a writer. It is completely fiction. It was completely created by me.”

But it turns out the story was inspired by a real-life experience of his own.

“Some years ago I lived in [Angolan capital] Luanda in an apartment that looks exactly like her apartment,” he explained.

I was working as a journalist and in a very hard context, and there was a lot of political problems and hard political problems with the government also. So I don’t want to go out, sometimes I really don’t want to go out, it’s very hard outside. And I start to think if I never go out, how I can live?

The it came to him – the image of an old woman stuck in her house. Agualusa even dreamt about the woman, and after he told a movie-making friend about it, he was encouraged to pen a script. It never got used, so some years later he returned to the story again.

He said that he and his character, Ludo, are different, and “we share this fear, but the fear is not exactly the same. She has this fear of the other, I have this fear of the political [events]“.

He calls her “a good person with the wrong ideas”, much of them racist. Ludo, he added, “is a kind of orphan of the Portuguese Empire, [who] was forgotten in Angola”.

After the book was published, Agualusa said he received letters from readers who knew of people with similar experiences. “So I think there’s a lot of people like that, that destroyed their lives because they are so terrified about the others. I think it’s a universal story, it’s not just in Angola.”

‘It’s a tragedy that we suffer everywhere’

The novel functions as a short history of this period of Angola’s past, but Agualusa also emphasises that he is not trying to represent everyone’s story here.

“Writers can just represent just themselves,” he said. “And of course our world, it’s just our world. It’s my Angola, it’s my Luanda… [But] it’s a kind of responsibility, yes.”

Ludo processes her world through writing. “She is a writer in that sense that all of us, we write to understand, to understand the other and to understand ourselves,” said Agualusa. “I like that idea that she has a very good library and so each book is a kind of window and she starts to burn the books, and so her world is extinguished, is diminished as she burns the books.”

She also suffers a personal tragedy that explains why she has chosen to hide herself away from the world.

“It’s a very specific story of course but it’s a tragedy that we suffer in Angola and in other countries. Everywhere, indeed,” said Agualusa. “I think books especially in countries as Angola that live under a totalitarian system, and people have no voice, I really think writers have this obligation to promote dialogue and promote discussions on important issues like that, violence against women.”

As a young boy, Agualusa read voraciously. He began writing properly in university – where so few of them wrote for the newspaper that they would make up bylines to make it look like there were more writers.

“And it was a good exercise because I developed different kinds of styles,” said Agualusa of that time. In a sense, it prepared him for a career where he now writes journalism, novels, plays and poetry.

‘You learn about your book’

His next novel has just been released in Portugal, and he and Hahn are about to start work on the English translation. Right now, there’s lots of debate over the title. “We don’t care about the rest of the book,” joked Agualusa’s translator, Daniel Hahn.

The act of translating is a difficult one. Many times during the process, they will come across words or phrases that don’t have an exact translation.

“It’s still rare to have writers who understand that,” said Hahn. “The thing you most want from your writer, you want them to be a great writer, you want them to be a nice person, all these things, but you also want them to understand what translation is.”

He gives the example of a word Agualusa uses, soledad. “I have to choose between [the translation] solitude and loneliness, it could be either,” said Hahn, by way of explanation.

And to have a writer who will discuss which one to choose is fine. To have a writer who will say ‘no, no but I mean both’? Well, you can mean both all you want, but then it has to be in Portuguese.

“I think the most interesting thing is you discover things about your book that you didn’t know previously, so you learn about your own book,” added Agualusa of the translation process.

Hahn said he gets why writers are nervous about translation. “I completely understand if you are a writer who is very careful and very deliberate and trying to do something specific and is completely in control of your language,” he said.

Agualusa said that as an author, within five minutes of conversation you’ll know whether a translator is good or not.

“So sometimes you understand he is not so good, but you can do nothing,” he shrugged.

Luckily, he and Hahn have a very fruitful working relationship, and the work on the forthcoming book won’t need to be as intense as it as when they first started working together.

That sense of trust is key, but so too is being able to show off Agualusa’s writing in the best way possible. Luckily, Hahn’s own gift for writing makes it so.

“The difficult bit is creating something that is alive, in a way that some writing is alive and some writing is dead, and you want to make something that is still alive,” said Hahn.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.