Conservation Community of Mozambique calls for 'immediate and decisive investigation and response' ...

Scientists find climate-resistant coral refuge in northern Mozambique – but say overfishing is killing it

Getty / Researcher found that reefs in northern Mozambique and the Quirimbas Islands support two types of refuges and environments that create the potential for coral to adapt to climate change. Pictured is a manta ray swimming with fish in Mozambique

Researchers have found that some coral reefs in northern Mozambique and the Quirimbas Islands have an environment that resists climate change.

However, the reefs are being overfished due to low compliance with fisheries law, killing the fish that help protect the reefs.

Identifying these climate-resistant reefs, called ‘reefs of hope,’ is a high priority among conservation groups as corals become ‘bleached’ across the planet due to higher water temperatures.

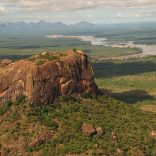

The Quirimbas Islands are an archipelago of about 32 islands off the coast on Northern Mozambique close to Pemba, reaching up all the way to the Tanzanian border.

The Quirimbas National Park encompasses the southern part of the archipelago, protecting coastal forest, mangroves and coral reefs.

To learn more about coral reefs and their response to climate change, researchers at the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) scientists studied 24 human communities and adjacent coral reef ecosystems in 5 countries of the southwestern Indian Ocean.

They used ecological measures of abundance and diversity of fishes and corals, estimated reef pristineness, and also determined the capacity of human communities to adapt to and cope with change.

They found that reefs in northern Mozambique and the Quirimbas Islands support two types of refuges and environments that create the potential for coral to adapt to climate change.

The first refuge is an environment that has enough variability for corals to adapt but lacks temperature extremes that would kill them.

The second one has deeper, cooler water but with the full spectrum of light that allows many species to thrive and avoid heat stress.

This second refuge is associated with shipping channels that support coastal people and centres of heavy fishing, and the researchers found that many nearby reefs weren’t sustainably fished, so fishers migrated to the second refuge for more profitable fishing.

These refuges, called ‘reefs of hope,’ are climate resistant reefs that are a high priority for conservation groups, as corals are collapsing across the world due to rising water temperatures.

The researchers found warning signs of overfishing including small fishes, a reduced number of species and more sea urchin and algae growth.

Excess growth of sea urchins and algae can wreak havoc in the sea – sea urchins can damage corals if not controlled by predators such as triggerfish, while algae can suffocate corals unless their growth is controlled by grazing fish species.

The Quirimbas Islands are an archipelago of about 32 islands off the coast on Northern Mozambique close to Pemba, reaching up all the way to the Tanzanian border +4

The Quirimbas Islands are an archipelago of about 32 islands off the coast on Northern Mozambique close to Pemba, reaching up all the way to the Tanzanian border

So to protect these ‘reefs of hope,’ the researchers recommend that coral refuge areas maintain a fish biomass of more than 500 kilograms (1,103 pounds) per hectare – the threshold to maintain ecological functions while also sustaining local fisheries.

‘Northern Mozambique Quirimbas reefs have a variety of refugia, environmental variability, and high diversity that give these reefs a high potential to adapt to rapid climate change,’ said Dr Tim McClanahan, WCS’s Senior Conservation Zoologist and lead author of the study.

‘If this region is to provide adaptive potential to climate change, fishing at a sustainable level and maintaining reef fish biomass, life histories, and functions is a high priority.’

While management recommendations have already been put in place, such as fishing gear restrictions, closing certain areas to fishing, and enforcing regulations in the Quirimbas National Park, the government has failed to implement these restrictions.

According to the researchers, properly managing marine protected areas (MPAs) continues to remain a challenge due to insufficient staff and money required to enforce management.

But despite these, a global commitment has been made to address the immediate threats facing coral reefs.

Last February, at the Economist World Ocean Summit in Bali, Indonesia, the ‘50 Reefs’ initiative was launched by the Global Change Institute of the University of Queensland and the Ocean Agency.

It brings together leading ocean, climate and marine scientists to develop a list of the 50 most critical coral reefs to protect, while leading conservation practitioners are working together to establish the best practices to protect these reefs.

Why does coral bleaching happen?

Corals have a symbiotic relationship with a tiny marine algae called ‘zooxanthellae’ that live inside and nourish them.

When sea surface temperatures rise, corals expel the colourful algae. The loss of the algae causes them to bleach and turn white.

While mildly bleached corals can recover if the temperature drops and the algae return, severely bleached corals die.

How they did the study

To conduct the research, WCS scientists studied 24 human communities and adjacent coral reef ecosystems in 5 countries of the southwestern Indian Ocean.

They used ecological measures of abundance and diversity of fishes and corals, estimated reef pristineness, and also determined the capacity of communities adjacent to reefs to cope with and adapt to change.

They also used web-based oceanographic and coral mortality data to predict each site’s environmental susceptibility to climate warming.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.