Sant’Egidio community willing to support peacekeeping in Mozambique

Charcoal on pedals – a long-suffering income that threatens Mozambique

Carvoeiros transport charcoal on their bicycles along Estrada Nacional 6 (EN6), in Chimoio, Mozambique, June 15, 2022. There are fewer and fewer forests and they are further and further away, a sign that the fight against climate change is even more difficult in an Africa where daily survival is more important than saving the earth's future. [Photo: André Catueira/Lusa]

Vasco Zacarias, 24, cycles 540 kilometres a week hauling 500 kilograms of charcoal in central Mozambique. His route is three times longer now than when he started in the business in 2016.

There are fewer and fewer forests and they are further and further away, he says. “We are carrying the charcoal a long way now,” he tells Lusa in Chimoio, the provincial capital of Manica province, in central Mozambique.

He has just arrived, sweating, in the city after seven hours riding a basic bicycle over rough roads.

The distance grew so much that, in 2018, Vasco Zacarias had to create an intermediate point at his home in Mucorodzi to divide in half the route from the ovens where the wood is transformed into charcoal to the final consumer.

The business earns him 250 meticais (just over three euros) for each sack of charcoal sold, money with which he pays for food, health and education expenses.

The massive demand for wood as fuel is among the activities that exert great pressure on forests, causing historic deforestation, according to the National Sustainable Development Fund (FNDS), one of several entities that have raised awareness of the problem.

A 2020 study by the non-governmental organisation Observatório do Meio Rural (OMR) highlighted in particular the risks of deforestation in Manica province, alongside Nampula and Zambézia, the most populous in the country.

Unlike the other charcoal worker, Alexandre Artur, he produces and sells his own charcoal, but the effort expended does not pay off due to the distances he now travels and the time the business consumes.

“Trees? There are no longer any nearby, so people are going very far to cut [them] and make charcoal,” he tells Lusa, explaining that he now has to wake up at three in the morning and cycle for six hours whenever there is charcoal to bring to Chimoio.

Along the way, he says, he faces the danger of attacks and animal bites in the woods and robbers on the roads.

There are people who take “up to three days to get here with charcoal”, says another charcoal worker, Pedro Augusto, adding, “the trees are visibly dying”.

Environmentalist Eugénio Fumane describes deforestation in Manica as a “serious problem” which is getting worse because of the pressure on forests exerted by charcoal workers.

Fumane says the government must “design good policies” to tackle deforestation and undertake sustainable reforestation actions.

“If cities adopt other sources [of fuel] to prepare their meals,” namely with “the government encouraging the use of cooking gas in the kitchen and reducing the cost of electricity, I think we will be able to reduce the problem,” says Fumane, who is also project manager of the Fórum Terra [Earth Forum] in Manica.

To survive, Fumane continues, charcoal workers cutting down fruit trees, especially mango trees, for charcoal production, putting orchard production at risk, a detail he uses to once again warn about the need for “serious reforestation policies”.

Manuel António, another environmentalist, this time from the Micaia Foundation, tells Lusa that, in his opinion, Mozambique has suffered severe damage from cyclones because of levels of deforestation.

“The trees also serve as windbreaks. Cutting down these trees means we will suffer: the wind will strike at infrastructure,” he explains.

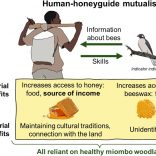

A project by the Micaia Foundation is helping rural communities in Sussundenga to protect trees by placing beehives on the trees to earn income from producing honey instead of selling charcoal.

Marketing is also part of the Sussundenga project, with the honey being sold to a supermarket chain.

But in the north of the province, alternatives like these never touch the life of Vasco Zacarias and his beat-up bicycle, and the charcoal worker maintains his weary routine.

“I load up three times a week – on Monday, Wednesday and Friday. The other days, I go to the forest,” he says as he counts the money from the sale of the first sack of charcoal of the day, shortly after arriving in Chimoio.

“It’s not always like that,” he tells Lusa, with the smile of someone who still expects profitable days from his business of charcoal on pedals.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.