Mozambique: Cabo Delgado, Nampula & Niassa Humanitarian Snapshot, as of August 2025

Mozambique. ‘Industry of suffering’, negotiations call, Rwandans take Awasse, Nyusi statement – By Joseph Hanlon

Map: VOA

In this issue

Cabo Delgado

- Aid creating ‘industry of suffering’

- Civil society call for negotiations

- Rwandans retake key road junction

- Nyusi blames aggressor who wants Moz poor

- Fura Rubies controls 683 sq km

Covid-19

- Record deaths & cases

Cabo Delgado

- Humanitarian aid creating ‘industry of suffering’ says bishop

“An industry of suffering, which takes advantage of the suffering of the people” can be created by humanitarian support organisations setting up heavy operating structures that pay high salaries to their workers. These entities can channel more resources to their machine than to the populations in need, the Bishop of Pemba Antonio Juliasse Sandramo warns. (DW 23 July)

Furthermore, in a country with endemic levels of corruption, humanitarian aid can be diverted, he added. “This risk exists, and with the levels that we have of corruption in Mozambique, the risk becomes greater.”

- Civil society group calls for negotiations

With government pushing so hard for a purely military victory, there has been little space for alternative voice. CDD (Centro para Democracia e Desenvolvimento; Democracy and Development Centre) yesterday (July 26) came out for “negotiating with violent extremists in Cabo Delgado”. The report, in English, is HERE

“If negotiations with the VEO [violent extremist organisation] in Cabo Delgado are well designed and managed they will be a vital tool for reducing violence and human rights abuses. Negotiations are likely to be even more productive when used as part of a comprehensive local and national strategy involving multiple, synchronised interventions that balance threats and incentives,” the report says.

CDD sees the insurgents as having three negotiating goals: One is “an end to persecution, marginalisation and land-grabbing, and better public services for the communities from where they originated.” The second would recognise that the insurgents’ goals are “primarily financial and socio-economic” and thus a demand will be “immediate employment, training and education opportunities.” The third would some form of “cultural and religious recognition.”

An important reason to negotiate with the insurgents is “preventing VEO from conducting collusive negotiations with other parties. … This is a key challenge in Cabo Delgado, in order to prevent the potential for Islamic State (IS) to directly influence/support the VEO.”

- Comment: In the end, we always talk to terrorists

Talking to Terrorists: How to end armed conflicts is a book by Jonathan Powell, who played a central role in negotiating a peace agreement in Northern Ireland in 1998. It looks at many negotiations with terrorists, including Renamo in Mozambique. Renamo kidnapped schoolchildren and burned people alive in buses in the 1980s, and now the former “terrorists” are the official opposition in parliament.

“Terrorism” is what the word says – it is to terrorise people, to make them afraid. It is the weapon of a weak opposition – Renamo four decades ago or the machababos now. But if there are serious grievances, terrorists can gain local approval. The attack on Palma showed a significant level of local support.

Civil wars that end in peace all end with negotiations and compromises. Military suppression just means the grievance and violence will bubble up again, somewhere, some time. Rwandan soldiers may be able to put the lid on, but without an agreement it will boil over again.

Richard Rands, an advisor to CDD, co-wrote the paper “Evolving doctrine and modus operandi: violent extremism in Cabo Delgado” (free) which we cited here two weeks ago. In it he argued the insurgents “believe that increased channels for political participation within the framework of national governance can be obtained through popular violent uprising.” And he stressed the insurgents are “not currently connected in any impactful way to IS.” That means there is still time to negotiate, before IS provides more military support and while the goals are still negotiable – jobs and political participation could be provided.

And as CDD suggests, smaller local negotiation would be a way to start. Local commanders are still local and are known to communities and to aid workers negotiating access. A start could be local cease fires and local settlements, giving insurgents a role in rebuilding. This has happened before. Local cease fires in 1990 and 1991 were an important background to the Renamo negotiations in Rome. Genuine local leaders (not Frelimo place people) could mediate and bring the two sides together.

Negotiations would be hard because there are many competing interests and hidden supporters of the civil war. But local starts – precisely talking to “terrorists” – could stop the war. But will that require concessions that Frelimo hopes to avoid through a military victory? jh

- Rwandans retake key Awasse road junction

In a region with few paved roads, control of those roads is a clear military goal. Awasse junction controls all movement in the north of Cabo Delgado: one road goes west to Mueda, one road goes east to Mocimboa da Praia, and the third road goes south to Macomia and Pemba. Insurgents have controlled the junction for a year. They set up an important base and destroyed the electricity transformer station and mobile phone links there, cutting electricity and restricting phone service to Mueda, Mocimboa, Palma and Nangade. Government troops held Diaca, 10 km to the west toward Mueda, but could not retake Awasse.

Rwandan troops have now retaken Awasse. The offensive appears to have started Thursday (22 July) and was continuing yesterday (26 July). Insurgents were killed but the number has apparently been exaggerated in some reports; probably around a dozen dead. (STV, Zitamar, MediaFax, Rhula 26, 27 July)

Government holds Macomia town, but not the roads north to Mueda and Awasse. Mediafax reports a platoon of 50 Rwandan soldiers was seen moving north from Macomia toward Chai, which is the edge of the insurgent controlled zone. The next step is probably to reopen the road from Chai to Awasse. That would allow an armoured force to move on the paved road east toward Mocimboa da Praia.

The map below shows the approximate current position, with insurgents controlling the area from the green line east to the sea. Mueda is at the left of the map, Mocimboa da Praia upper right, and Macomia bottom. We assume that the Rwandan and Mozambican military will try to retake the N380 north of Chai and east of Awasse. Awasse to Mocimboa is 40 km.

- Nyusi blames ‘aggressors that want to steal our resources’, rejecting poverty & exclusion as causes of war

The Cabo Delgado war is caused by aggressors who “want to keep Mozambicans in poverty and want to steal our resources,” said President Filipe Nyusi in a speech to the nation Sunday (25 July). He rejected “scholars of terrorism” who blame poverty and exclusion.

But he went on to say that “lack of employment opportunities is a motivating factor”. Thus action “to prevent and control violent extremism, consists in promoting intensive programs to promote development, training and creation of employment opportunities” though the Northern Integrated Development Agency (ADIN). It is already implementing a $100 mn “program of prevention and resilience against conflicts”.

(The full text in Portuguese is HERE and an unofficial translation to English by Miguel de Brito is HERE.

Outside of Cabo Degado, actions of the Defence and Security Forces (FDS) mean “that Mozambique continues to be a stable country, with State, private sector and civil society institutions functioning normally.” But help is needed in Cabo Delgado, and Nyusi went on to cite support and training for armed forces of Zanu in Zimbabwe, ANC in South Africa, Uganda, and East Timor.

Nyusi accuses the insurgents of “genocide” and says the terrorism in Cabo Delgado “is a phenomenon little known in Mozambique,” which does seem to ignore the 1982-92 Renamo war.

The president also noted the damage done by the war:

- 826,000 people displaced due to the war

- 39 health units closed, meaning “the districts of Mocimboa da Praia, Quissanga, Macomia, Muidumbe and Palma do not have any health services.”

- “The suspension of activity [by Total] had a direct impact of approximately $116 mn in turnover; 3,250 workers, including direct Total workers, were left with suspended employment contracts.”

Many commanders. South Africa will lead the troops of the Southern African Development Community (SADC) in Cabo Delgado. Each SADC country will command its own forces, with South Africa, as the country with the largest force, in overall control, declared the Chief of Staff of the Mozambican Armed Forces (FADM), Joaquim Mangrasse, on 23 July. (AIM 23, 24 July)

Mozambique will have an overall coordination role, and nine Mozambican officers have been chosen to be in all positions of coordination.

South African General Xolani Mankayi will command the SADC forces. He headed the 43 Brigade, the rapid intervention unit of the South African National Defence Force (SANDF). He has been training his intervention unit for a year. (This newsletter 3 Aug 2020)

Mpho Molomo of Botswana is the special representative of the SADC Standby Force, who is effectively the diplomatic face of the mission.

Isaura Maquina, Montepuez district administrator, blames the victims, saying some displaced people are not receiving support because of the opportunism of other IDPs who are hoarding products donated by the Government and humanitarian organizations. “Displaced families register in different villages. The family registers, the mother registers, the son registers, the father registers; they end up being several households in one,” she complains. (O Pais 20 July) Comment: This must be happening, because the number of registered displaced is larger than the entire population of the war zone, and there are indications of aid being sold. But in many areas, multiple registration can only be done with the connivance of local Frelimo officials, who will take a cut. jh

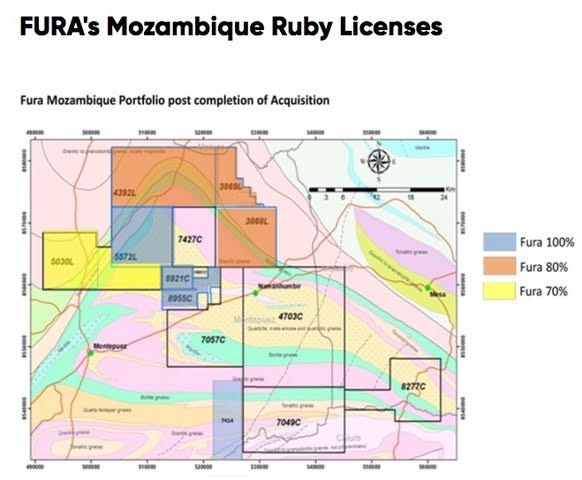

- Fura rubies controls 683 sq km adjoining Montepuez Ruby Mining

Dubai-based Fura Gems is taking over various mining companies and licences in Montepuez to give it a huge, 683 square kilometre ruby mining concession, and will hold its first ruby auction next month, Dev Shetty, Founder and CEO, told Fortune India (23 July). The Fura area is just northwest of the controversial Gemfields/Montepuez Ruby Mining (MRM) site.

The map below shows the road from Montepuez city through Namanhumbir and east toward Pemba. Block 4703C which includes Namanhumbir is the 350 sq km MRM mine. But Gemfields also controls the four other clear blocks (7427C, 7057C, 7049C and 8277C which totals 490 sq km. Fura controls the eight coloured blocks, all but one north of the road.

In 2019, Jerry Maquenzi of the Rural Observatory (OMR) wrote a paper on the poverty in this zone of giant mines (Portuguese only) “Pobreza e desigualdades em zonas de penetracao de grandes projectos: Estudo de caso em Namanhumbir”.

Covid-19

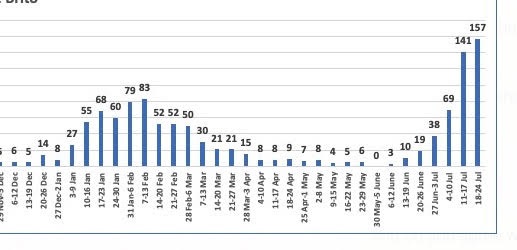

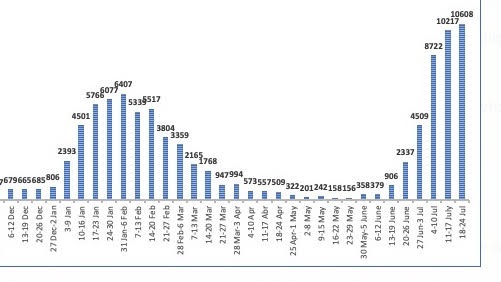

- Record deaths & cases, but perhaps peak is being reached

New Covid-19 cases continue at almost double the peak levels of January and February. The rapid rise has slowed, but numbers are not going down. In the Ministry of Health report this afternoon (27 July) covering the past 24 hours, the number of deaths was 34, the highest so far. The number of new cases was 1,703, the 4th highest. (The peak was 2154 on 22 July)

“In a very short space of time, the country could find itself facing a lack of beds, unless we change our behaviour and implement adequately the Covid-19 prevention measures”, Health Minister Armindo Tiago, told reporters 24 July in Quelimane. In some provinces, hospitals are in danger of running out of intensive care beds for Covid-19 patients. “The hospitalisation capacity in Maputo province is already above 100%, and in the other provinces, although less than 70% has been reached, we must understand that the daily level of hospital admissions is very high”, said Tiago.

Ministry of Health said today that 81 more people were hospitalised with only 33 leaving, meaning 473 Covid-19 patients are now hospitalised. In Matola 49 patients are hospitalised, with only 40 intensive care beds.

Weekly deaths from Covid-19 to 24 July (Miguel de Brito graph)

Weekly new cases of Covid-19 to 24 July (Miguel de Brito graph)

Other reading

Mozambique: fears of escalating conflict as foreign troops clash with Islamists, Jason Burke, The Guardian, 26 July. Quotes Dino Mahtani of International Crisis Group: “Military pressure can degrade and erode [the insurgency in Mozambique] but ultimately this is a conflict that needs resolution dialogue”.

How Frelimo betrayed Samora Machel’s dream of a free Mozambique, David Matsinhe, The Conversation, 18 July.

Analysis: Mozambique’s gas ambitions rest on distant hope of peace, Emma Rumney and David Lewis, Reuters, 23 July.

By Joseph Hanlon

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.