Meet the human statues turning unemployment into art on Maputo’s streets

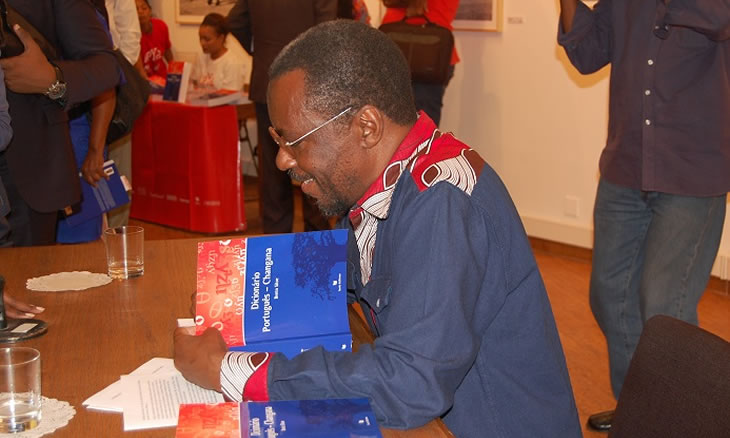

17,000 words translated from Portuguese to Shangaan – Mozambique

Photo: O País

A total of 17,000 Portuguese words have been translated into Changana, the language most widely spoken in the Mozambican capital, in the new dictionary by linguist and university professor Bento Sitoe.

Apart from the omnipresent “Khanimambu”, which means “Thank you”, the new bilingual dictionary makes it to construct numerous everyday expressions, such as “Ripelile va ka hina”, or “Good evening, compatriots”, the author told Lusa.

Changana is a mix of several thousand-year-old sub-Saharan Africa Bantu languages originating from Cameroon to Cape Town in South Africa. It is estimated that there are more than three million Shangaan speakers in Southern Africa, in Mozambique, South Africa (where it is one of the official languages), Swaziland and Zimbabwe.

The target audience of the new dictionary are teacher-trainers working in Mozambican languages, tutors and students of bilingual education, and media and translation professionals, Sitoe says.

And with the predicted “new wave of investments in the country,” especially in the area of gas and oil, “published lexicons will be important” for those who are considering investing here.

In addition to the new Portuguese-Changana dictionary, Sitoe is also the author of the Changana-Portuguese dictionary, published by Texto Editores in 2012, with more than 15,000 entries, a revised and expanded edition of the 1996, 12,000-word edition.

The idea is not new: there is an English-Changana dictionary published in South Africa, “but that has only 3,000 entries,” he adds.

To compile the dictionaries, Sitoe consulted Changana speakers from many different regions, noting that there is a false idea that Changana has not been standardised and therefore cannot be legislated.

“For years, Eduardo Mondlane University in Maputo has standardised 19 languages, and every 10 years, it reviews these standards. There is uniformity, not spoken, but written, which is consensual,” he explains.

One of the reasons local languages survive is that they have many speakers in Mozambique and Mozambicans have a “very strong” sense of belonging, and value what is uniquely theirs.

“What happens is that a speaker of a language like Ronga,” which is spoken in southern Mozambique and is similar to Changana, “stands out, speaks with force, letting differences appear with the others.”

“Some even say: either you speak in Ronga or there is no conversation. It is this valuing that keeps local languages alive”, he explains.

In 1978, Sitoe attempted to publish a novel, Zabelana, in Changana, and was almost prevented by the post-independence authorities’ view that it was ‘triballist’ and contrary to “national unity” to publish a book in a local language.

Only thanks to then-Minister of Information Jose Luis Cabaço was the work published in Changana – but only after its contents were vetted in a Portuguese translation.

After 30 years, the challenges are different.

With a wave of foreign investments in prospect, the terminology and vocabulary of other languages – such as English – is already applied to projects in Mozambique, often on the Internet.

But Bento Sitoe says he does not fear for the local languages. On the contrary, he supports the entrance of more languages in the country, so that they too become part of Mozambican culture, like Portuguese.

“We want Portuguese to be spoken here and well-rooted. It is a language that is part of the culture of Mozambique,” he concludes.

Leave a Reply

Be the First to Comment!

You must be logged in to post a comment.

You must be logged in to post a comment.